Ronald F. Inglehart

Nguyễn Quang A dịch

PHỤ LỤC 1: NGHỊCH LÝ EASTERLIN

Nghịch lý Easterlin nguyên bản cho rằng người dân của các nước giàu không có các mức hài lòng với cuộc sống cao hơn người dân của các nước nghèo. Phân tích một mẫu dữ liệu từ 14 nước được khảo sát trong các năm 1950, Easterlin (1974)1 đã tìm thấy hầu như không sự tương quan nào giữa tổng sản phẩm quốc gia (GNP) trên đầu người và sự hài lòng với cuộc sống: mặc dù Tây Đức đã giàu gấp đôi Ireland, những người Irish đã cho thấy các mức hài lòng với cuộc sống cao hơn. Ông kết luận rằng sự vắng mặt của một tương quan giữa GNP/đầu người và sự an lạc chủ quan có nghĩa rằng sự phát triển kinh tế đã không cải thiện số phận con người – một phát hiện được trích dẫn rộng rãi như “Nghịch lý Easterlin.”

Nhưng phát hiện của Easterlin dựa vào một mẫu tương đối nhỏ gồm chủ yếu các nước giàu. Inglehart (1990)2 phân tích dữ liệu từ một mẫu rộng hơn của các nước và đã thấy một tương quan 0,67 giữa GNP và sự hài lòng với cuộc sống. Các nghiên cứu tiếp sau dựa vào các dải rộng của các nước đã xác nhận phát hiện này: ngược với Nghịch lý Easterlin gốc, các nước giàu quả thực có các mức an lạc chủ quan cao hơn các nước nghèo.

Sau khi các phát hiện này được công bố, Easterlin đã lập lại nghịch lý để cho rằng sự phát triển kinh tế không đem lại những sự tăng lên về sự an lạc chủ quan theo thời gian (mà ngụ ý rằng tương quan lát cắt ngang mạnh phải là do sự trùng hợp thuần túy). Vì chuỗi thời gian dài nhất của các số đo hạnh phúc (cho đến nay) đã đến từ Hoa Kỳ và nó cho thấy không sự tăng lên nào từ 1946 cho đến sự đo gần đây nhất, khẳng định này có vẻ có lý.

Nhưng Inglehart, Foa, Peterson and Welzel (2008) phân tích dữ liệu từ rất nhiều nước phủ toàn bộ dải phát triển, được thu thập từ 1981 đến 2008 – tìm thấy rằng cả hạnh phúc và sự hài lòng với cuộc sống đã tăng lên trong tuyệt đại đa số các nước. Như Hình 8.2 chứng minh, sự hài lòng với cuộc sống tăng lên mạnh khi chúng ta chuyển từ các nước rất nghèo tới các nước thịnh vượng khiêm tốn và sau đó phẳng ra.

Easterlin (2009) cho rằng sự tăng rộng khắp về hạnh phúc và sự hài lòng với cuộc sống từ 1981 đến 2008 là do một sự thay đổi về các chỉ dẫn cho người phỏng vấn được dùng với câu hỏi hạnh phúc:

Giữa đợt 2 và đợt 3 của WVS (từ 1990 đến 1995) chỉ dẫn cho những người phỏng vấn để thay phiên thứ tự sự lựa chọn câu trả lời từ một người trả lời sang người tiếp theo đã bị bỏ đi. Do đó một tác động ưu thế đầu tiên (primacy effect) được kích hoạt: một xu hướng cho những người trả lời để thiên vị lựa chọn sớm hơn các lựa chọn muộn – khiến cho nhiều người chọn “rất hạnh phúc” và ít người chọn “không hạnh phúc chút nào.” Các lựa chọn hạnh phúc bị thiên vị này hướng lên cho nên hạnh phúc tăng tuy sự hài lòng với cuộc sống đã giảm trong các nước nguyên-cộng sản.3

Nếu giả như sự tăng về hạnh phúc là do sự thay đổi này về các chỉ dẫn người phỏng vấn, dữ liệu sẽ cho thấy một sự tăng một lần khổng lồ về hạnh phúc trong khảo sát 1995, và không sự tăng lên nào trong các đợt kháo sát sớm hơn và muộn hơn. Nhưng dữ liệu không cho thấy hình mẫu nào như vậy: như Hình 8.6 chứng minh, hạnh phúc đã tăng đều đặn từ 1981 đến 2005 với không sự dấy lên có thể nhận biết nào trong năm 1995.

Hơn nữa, sự thay đổi về các chỉ dẫn người phỏng vấn cho câu hỏi hạnh phúc đã có lẽ không thể giải thích sự tăng lên về sự hài lòng với cuộc sống. Easterlin không thừa nhận sự thực này. Thay vào đó ông bình luận rằng sự hài lòng với cuộc sống đã giảm trong các nước nguyên-cộng sản, cứ như đấy là hình mẫu phổ biến (mà rõ ràng là không).

Easterlin đang thử thanh minh một sự tăng mạnh về hạnh phúc bằng việc quy nó cho các tác động ưu thế đầu tiên, mà bình thường có ít tác động trừ phi người ta đang xử lý các đề tài mà về nó người trả lời không có ý kiến thực – trong trường hợp đó, người ta cũng thường nhận được lượng lớn của sự không-trả lời. Các câu hỏi về hạnh phúc và sự hài lòng với cuộc sống của một người là các chủ đề mà gần như tất cả mọi người đều có một ý kiến, và họ tạo ra các mức không-trả lời cực kỳ thấp: thay cho 30–40 phần trăm không-trả lời tìm thấy trong việc trả lời cho các câu hỏi không rõ hay gây lẫn lộn, tỷ lệ không-trả lời cho câu hỏi hạnh phúc là khoảng một phần trăm. Công dân trung bình có thể không có ý kiến rõ ràng về các nguyên nhân của sự nóng lên toàn cầu – nhưng biết kỹ liệu ông ta hay bà ta có hạnh phúc hay bất hạnh. Chỉ dẫn người phỏng vấn bị bỏ đi bởi vì nó được kỳ vọng không có tác động nào. Các kết quả kinh nghiệm trong Hình 8.6 ủng hộ sự kỳ vọng này: việc bỏ nó trong năm 1995 đã không có tác động có thể nhận biết nào.

Nghịch lý Easterlin là không thể đứng vững. Sự phát triển kinh tế có dường như cải thiện số phận con người – tuy nó làm vậy trên một đường cong lợi tức giảm dần, và (như Chương 8 chứng minh) chỉ là một trong nhiều nhân tố ảnh hưởng đến hạnh phúc và sự hài lòng với cuộc sống.

PHỤ LỤC 2

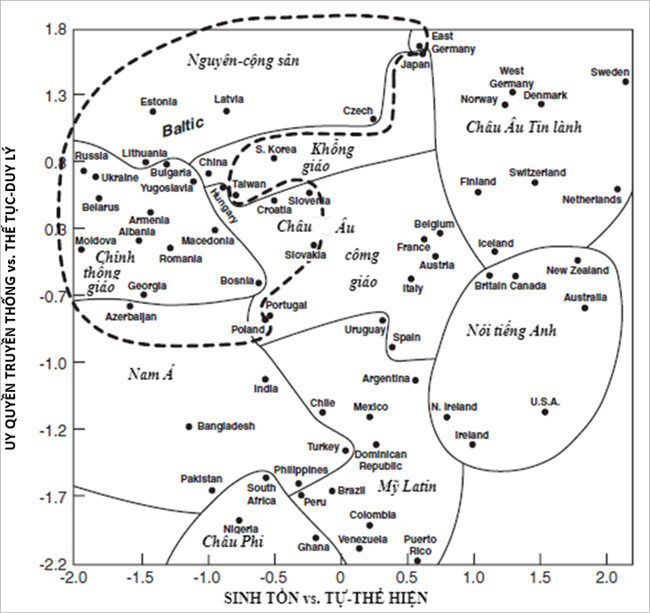

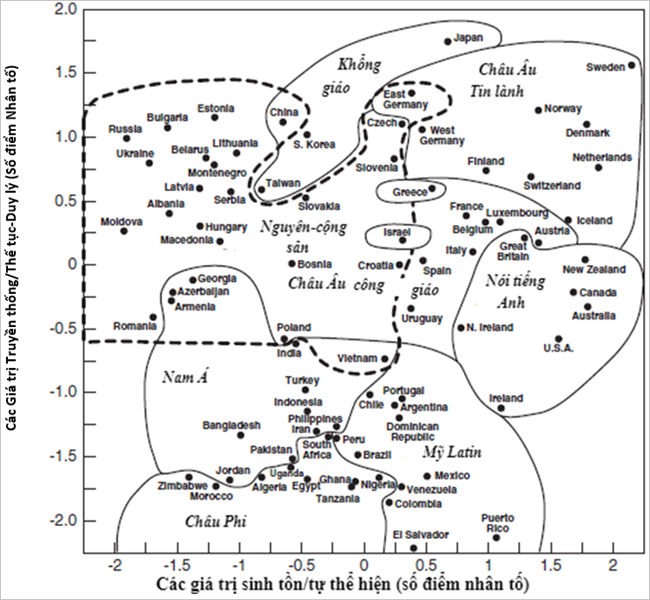

Hình A2.1 Bản đồ văn hóa toàn cầu từ 1995

Hình A2.2 Bản đồ văn hóa toàn cầu từ 2000

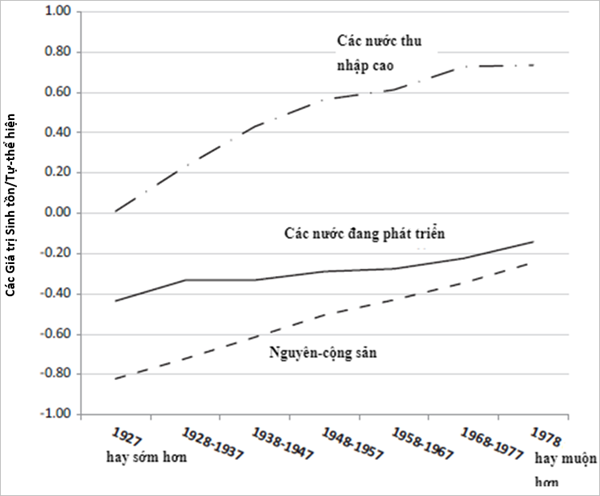

Hình A2.3 Các sự khác biệt liên quan đến tuổi về các giá trị Sinh tồn/Tự-thể hiện, trong ba kiểu xã hội.

Dữ liệu từ các nước sau được sử dụng:

Các nước thu nhập cao (vào năm 1992): Andorra, Australia, Austria, Bỉ, Canada, Cyprus, Đan Mạch, Phần Lan, Pháp, Đức, nước Anh, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Nhật Bản, Luxembourg, Hà Lan, New Zealand, Bắc Ireland, Na Uy, Singapore, Tây Ban Nha, Thụy Điển, Thụy Sĩ, Đài Loan, Hoa Kỳ.

Các nước đang phát triển (vào năm 1992): Algeria, Argentina, Bangladesh, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Chile, Trung Quốc, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Ai Cập, Ethiopia, Ghana, Hy Lạp, Guatemala, Ấn Độ, Indonesia, Jordan, Malaysia, Mali, Malta, Mexico, Morocco, Nigeria, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Portugal, Rwanda, Nam Phi, Hàn Quốc, Tanzania, Thái Lan, Trinidad và Tobago, Thổ Nhĩ Kỳ, Uganda, Uruguay, Venezuela, Việt Nam , Zambia, Zimbabwe.

Các nước nguyên-cộng sản: Albania, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cộng hòa Czech, Estonia, Georgia, Hungar y, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Ba Lan, Rumania, Nga, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Ukraine.

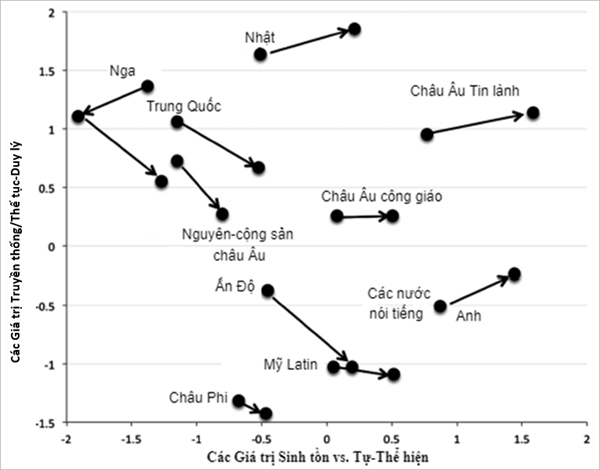

Hình A2.4 Sự thay đổi thuần trên hai chiều chính của sự biến thiên ngang-văn hóa từ khảo sát sẵn có sớm nhất đến muộn nhất (1981–2014) trong mười kiểu xã hội.

Các nước được bao gồm trong mỗi trong mười kiểu xã hội là:

Các nước nguyên-cộng sản: Albania (1998–2008), Azerbaijan (1997–2011), Armenia (1997–2011), Bosnia (1998–2008), Bulgaria (1991–2008), Belarus (1990–2008), Croatia (1996–2008), Czech Republic (1991–2008), Estonia (1996– 2011), Georgia (1996–2009), Hungary (1991–2008), Kyrgyzstan (2003–2011), Latvia (1996–2008), Lithuania (1997–2008), Moldova (1996–2008), Ba Lan (1990–2012), Rumania (1998–2012), Serbia (1996–2008), Slovakia (1991–2008), Slovenia (1992–2011), Ukraine (1996–2011).

Các nước Mỹ-Latin: Argentina (1984–2006), Brazil (1991–2006), Chile (1990–2011), Colombia (2005–2011), Mexico (1981–2012), Peru (1996–2012), Uruguay (1996–2011), Venezuela (1996–2000).

Các nước châu Phi: Ghana (2007–2012), Morocco (2007–2011), Nigeria (1990–2011), Rwanda (2007–2012), Nam Phi (1982–2006), Zimbabwe (2001–2012).

Các nước Âu châu công giáo: Austria (1990–2008), Bỉ (1981–2009), Pháp (1981–2008), Hy Lạp (1999–2008), Italy (1981–2005), Luxembourg (1999–2008), Portugal (1990–2008), Tây Ban Nha (1981–2011).

Các nước Âu châu Tin Lành: Đan Mạch (1981–2008), Phần Lan (1990–2009), Đức (1981–2008), Iceland (1990–2009), Hà Lan (1981–2012), Na Uy (1982–2008), Thụy Điển (1982–2011), Thụy Sĩ (1996–2008).

Các nước nói tiếng Anh: Australia (1981–2012), Canada (1982–2006), Anh (1981–2009), Ireland (1981–2008), New Zealand (1998–2011), Northern Ireland (1981–2008), Hoa Kỳ (1982–2011).

PHỤ LỤC 3

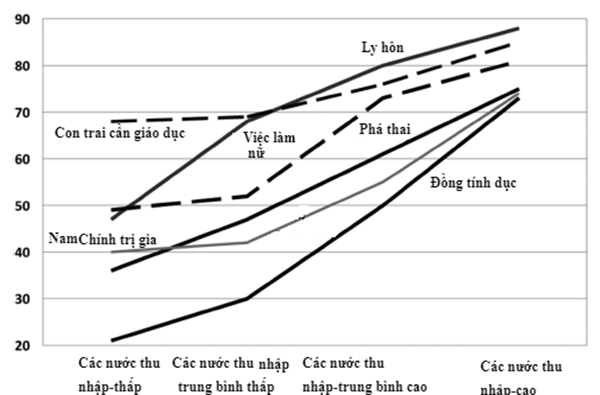

Hình A3.1 Sáu khía cạnh khoan dung, theo mức phát triển kinh tế. Tỷ lệ phần trăm bày tỏ quan điểm khoan dung về chủ đề cho trước.

Các nước bao gồm trong mỗi loại là:

Các nước thu nhập-thấp (như được World Bank phân loại trong 2000): Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Armenia, Ethiopia, Georgia, Ghana, Ấn Độ, Indonesia, Kyrgyzstan, Mali, Moldova, Nigeria, Pakistan, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Việt Nam, Zambia, Zimbabwe; Các nước thu nhập trung bình thấp: Albania, Algeria, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Belarus, Trung Quốc, Colombia, Dominican Rep., Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Guatemala, Iran, Iraq Kazakhstan, Jordan, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Morocco, Peru, Philippines, Rumania, Nga, Serbia, Thái Lan, Tunisia, Thổ Nhĩ Kỳ; Các nước thu nhập trung bình cao: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Croatia, Czech Rep., Estonia, Hungary, Hàn Quốc, Malaysia, Malta, Mexico, Ba Lan, Puerto Rico, Saudi Arabia, Slovakia, Nam Phi, Đài Loan, Trinidad, Uruguay, Venezuela; Các nước thu nhập -cao: Australia, Austria, Bỉ, Canada, Cyprus, Đan Mạch, Phần Lan, Pháp, Đức, Hy Lạp, Hồng Kông, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Nhật Bản, Luxembourg, Hà Lan, New Zealand, Na Uy, Portugal, Singapore, Slovenia, Tây Ban Nha, Thụy Điển, Thụy Sĩ, Vương quốc Anh, Hoa Kỳ.

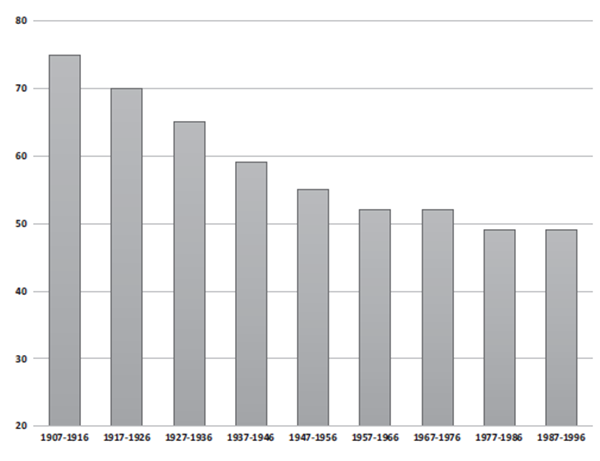

Hình A4.1 Tính bài ngoại và sự thay đổi giữa thế hệ

.

“Khi việc làm khan hiếm, các chủ sử dụng lao động phải trao ưu tiên cho những người của nước này hơn những người di cư” (phần trăm đồng ý theo năm sinh trong 26 nước thu nhập-cao).

Nguồn: Dựa vào tất cả dữ liệu Khảo sát Giá trị sẵn có từ tất cả các nước mà World Bank phân loại như các nước “thu nhập-cao” trong năm 1990 (chúng tôi sử dụng sự phân loại 1990 bởi vì dính líu đến thời gian trễ giữa thế hệ ở đây). Các nước là Andorra, Australia, Austria, Bỉ, Canada, Cyprus (Hy Lạp), Đan Mạch, Phần Lan, Pháp, Đức, nước Anh, Hồng Kông, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Nhật Bản, Luxembourg, Hà Lan, New Zealand, Qatar, Singapore, Tây Ban Nha, Thụy Điển, Đài Loan và Hoa Kỳ. Tổng số những người trả lời là 122.008.

PHỤ LỤC 5

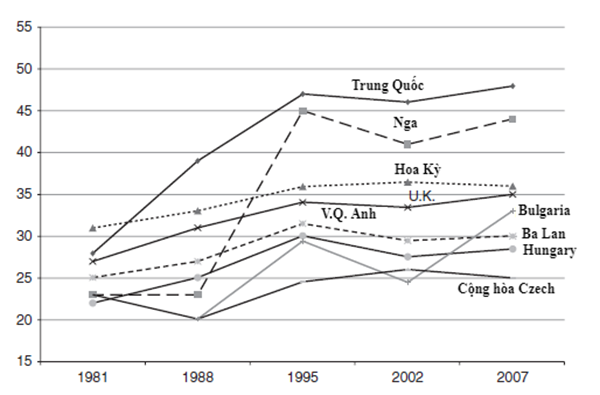

Hình A5.1 Các xu hướng bất bình đẳng thu nhập thuần của hộ gia đình: Nga, Trung Quốc và phương Tây, 1981–2007. Trục dọc cho thấy các chỉ số Gini.

Nguồn: dữ liệu từ Whyte, 2014.

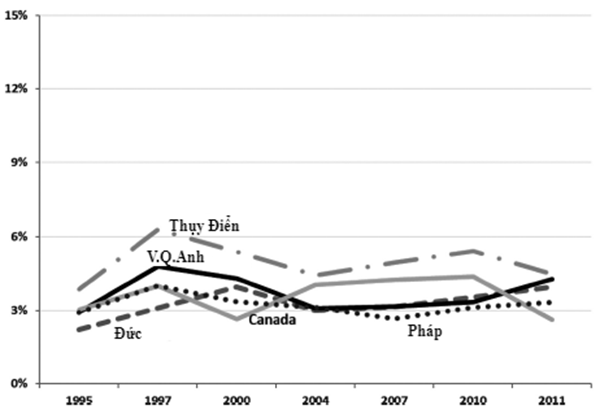

Hình A5.2 Tỷ lệ phần trăm của tổng việc làm trong khu vực thông tin và công nghệ truyền thông trong năm nền kinh tế tiên tiến, 1995–2011.

Nguồn: OECD (2014).

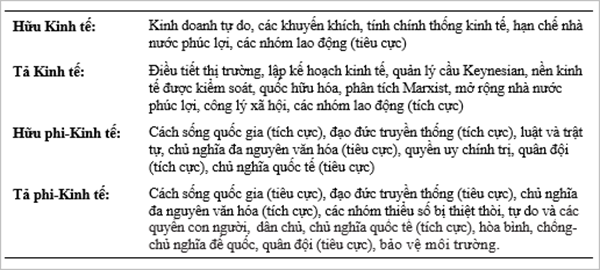

Bảng A5.1 Zakharov (2016) đã mã hóa thế nào các vấn đề cho trước như kinh tế hay phi-kinh tế từ các loại được dùng trong bộ dữ liệu Comparative Party Manifestos (So sánh Tuyên ngôn Đảng)

Phụ lục 1 Nghịch lý Easterlin

1 Easterlin, Richard A., 1974. “Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot?” in P. A. David and M. Reder (eds.), Nations, Households, and Economic Growth. New York: Academic Press, 98–125.

2 Inglehart, Ronald, 1990. Cultural Shift in Advanced Industrial Society. Princeton: Princeton University Press: 31–32.

3 Easterlin, Richard A., 2009. “Lost in Transition: Life Satisfaction on the Road to Capitalism.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 71: 130–145.

TÀI LIỆU THAM KHẢO

Abramson, Paul and Ronald F. Inglehart, 1995. Value Change in Global

Perspective. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Abramson, Paul, John Aldrich, Brad Gomez and David Rohde, 2015. Change and Continuity in the 2012 Elections. Sage: Los Angeles.

Acemoglu, Daron and James A. Robinson, 2006a. “De Facto Political Power and Institutional Persistence,” American Economic Review 96, 2: 326–330.

Acemoglu, Daron and James A. Robinson, 2006b. Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press. Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson, James A. Robinson and Pierre Yared, 2008. “Income and Democracy,” American Economic Review 98, 3: 808–842.

Adorno, Theodor W., Else Frenkel-Brunswik, Daniel J. Levinson and R. Nevitt Sanford, 1950. The Authoritarian Personality. New York: Harper & Row. Africa Progress Report, 2012. Jobs, Justice, and Equity. Geneva: Africa Progress Panel.

Aldridge,A.,2000.Religion in the ContemporaryWorld.Cambridge: Polity Press.

Almond, Gabriel A. and Sidney Verba, 1963. The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Andersen, Robert and Tina Fetner. 2008. “Cohort Differences in Tolerance of Homosexuality,” Public Opinion Quarterly 72, 2: 311–330.

Andrews, Edmund L., 2008. “Greenspan Concedes Error on Regulation,” New York Times, October 23: B1.

Andrews, Frank M. and Stephen B. Withey, 1976. Social Indicators of Wellbeing New York: Plenum.

Angell, Norman, 1933 [1909]. The Great Illusion. London: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Autor, David, H. and David Dorn, 2013. “The Growth of Low-Skill Service Jobs and the Polarization of the US Labor Market,” The American Economic Review 103, 5: 1553–1597.

Barber, Nigel. 2011. “A Cross-national Test of the Uncertainty Hypothesis of Religious Belief,” Cross-Cultural Research 45, 3: 318–333.

Barnes, Samuel H. and Max Kaase (eds.), 1979. Political Action: Mass Participation in Five Western Democracies. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Barro, Robert J., 1999. “Determinants of Democracy,” Journal of PoliticalEconomy 107, S6: 158–183.

Bednar, Jenna, Aaron Bramson, Andrea Jones-Rooy and Scott Page, 2010. “Emergent Cultural Signatures and Persistent Diversity,” Rationality and Society 22, 4: 407–444.

Bell, Daniel, 1973. The Coming of Post-Industrial Society. New York: Basic Books.

Benjamin, Daniel J., David Cesarini, Matthijs J. H. M. van der Loos, Christopher T. Dawes, Philipp D. Koellinger, Patrik K. E. Magnusson, Christopher F. Chabris et al., 2012. “The Genetic Architecture of Economic and Political Preferences,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, 21: 8026–8031.

Betz, Hans-Georg, 1994. Radical Right-wing Populism in Western Europe. New York: Springer.

Billiet, Jaak, Bart Meuleman and Hans De Witte, 2014. “The Relationship between Ethnic Threat and Economic Insecurity in Times of Economic Crisis: Analysis of European Social Survey Data,” Migration Studies 2, 2: 135–161.

Boix, Carles, 2003. Democracy and Redistribution. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Boix, Carles and Susan C. Stokes, 2003. “Endogenous Democratization,” World Politics 55, 4: 517–549.

Böltken, Ferdinand and Wolfgang Jagodzinski, 1985. “In an Environment of Insecurity: Postmaterialism in the European Community, 1970–1980,” Comparative Political Studies 17 (January): 453–484.

Borre, Ole, 1984. “Critical Electoral Change in Scandinavia,” in Russell J.

Dalton, Scott C. Flanagan and Paul Allen Beck (eds.), Electoral Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Princeton: Princeton University Press: 330–364.

Bradley, David, Evelyne Huber, Stephanie Moller, François Nielsen and John D. Stephens, 2003. “Distribution and Redistribution in Postindustrial Democracies,” World Politics 55, 2: 193–228.

Brickman, Philip and Donald T. Campbell, 1981. “Hedonic Relativism and Planning the Good Society,” in M. Appley (ed.), Adaptation-level Theory. New York: Academic Press, 287–305.

British Election Survey. Available at www.britishelectionstudy.com/ (accessed October 28, 2017).

Broadberry, Stephen and Kevin H. O’Rourke (eds.), 2010. The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Europe: 1700–1870. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brockmann, Hilke, Jan Delhey, Christian Welzel and Hao Yuan, 2009. “The China Puzzle: Falling Happiness in a Rising Economy,” Journal of Happiness Studies 10, 4: 387–405.

Bruce, Steve, 1992. “Pluralism and Religious Vitality,” in Steve Bruce (ed.), Religion and Modernization: Sociologists and Historians Debate the Secularization Thesis. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 170–194.

Brynjolfsson, Erik and Andrew McAfee, 2014. The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. Available at: https://data.bls.gov/pdq/querytool.jsp?survey=ln (accessed October 28, 2017).

Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1983. “Perceptions Reviewed,” Bureau of LaborStatistics Monthly Labor Review: April: 21–24.

Burkhart, Ross E. and Michael S. Lewis-Beck, 1994. “Comparative Democracy: The Economic Development Thesis,” American Political Science Review 88, 4: 903–910.

Case,Anne and Angus Deaton, 2015.“Rising Morbidity and Mortality in Midlife among White Non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st Century,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, no. 49: 15078–15083.

Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca, Paolo Menozzi and Alberto Piazza, 1994. The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Center for Systemic Peace. 2014. Polity IV Annual Time Series, 1800–2014.

Chenoweth, Erica and Kathleen Gallagher Cunningham, 2013. “Understanding Nonviolent Resistance,” Journal of Peace Research 5, 3: 271–276.

Chetty, Raj, David Grusky, Maximilian Hell, Nathaniel Hendren, Robert Manduca and Jimmy Narang, 2016. “The Fading American Dream: Trends in Absolute Income Mobility since 1940,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 22910.

Chiao, Joan Y. and Katherine D. Blizinsky, 2009. “Culture–Gene Coevolution of Individualism–Collectivism and the Serotonin Transporter Gene,” Proceedings of the Royal Society B 277, 1681: 529–553.

Christie, R. E. and Jahoda, M. E., 1954. Studies in the Scope and Method of“The authoritarian personality,” Glencoe: The Free Press.

Cingranelli, David L., David L. Richards and K. Chad Clay, 2014. “The CIRI Human Rights Dataset.” Available at www.humanrightsdata.com (accessed October 28, 2017).

Cummins, Robert A. and Helen Nistico, 2002. “Maintaining Life Satisfaction: The Role of Positive Cognitive Bias,” Journal of Happiness studies 3, 1: 37–69.

Dafoe, Allen and Bruce Russett, 2013. “Does Capitalism Account for the Democratic Peace? The Evidence Says No,” in Gerald Schneider and Nils Petter Gleditsch (eds.), Assessing the Capitalist Peace. New York: Routledge:110–126.

Dafoe, Allen, 2011. “Statistical Critiques of the Democratic Peace: Caveat Emptor,” American Journal of Political Science 55, 2: 247–262. Dahl, Robert A., 1971. Polyarchy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Dalton, Russell J., Scott Flanagan and Paul A. Beck (eds.), 1984. Electoral Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Davidson, Richard J. and Antoine Lutz, 2008. “Buddha’s Brain: Neuroplasticity and Meditation,” IEEE Signal Process Magazine 25, 1: 166–174.

De Martino, Benedetto, Dharshan Kumaran, Ben Seymour and Raymond J. Dolan, 2006. “Frames, Biases, and Rational Decision-making in the Human Brain,” Science 313, 5787: 684–687.

De Waal, Frans B. M., 1995. “Bonobo Sex and Society,” Scientific American 272, 3: 82–88.

Deutsch, Karl W., 1961. “Social Mobilization and Political Development,” American Political Science Review 55, 3: 493–514.

Deutsch, Karl W., 1966. Nationalism and Social Communication. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Diener, Ed and Richard E. Lucas, 1999. “Personality and Subjective Wellbeing,” in Daniel Kahneman, Edward Diener and Norbert Schwarz (eds.), Well-being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 213–229.

Diener, Ed., Eunkook M. Suh, Richard E. Lucas and Heidi L. Smith, 1999. “Subjective Well being: Three Decades of Progress,” Psychological Bulletin 125, 2: 276–302.

Diener, Ed., Richard E. Lucas and Christie N. Scollon, 2006. “Beyond the Hedonic Treadmill: Revising the Adaptation Theory of Well-being,” American Psychologist 61, 4: 305–314.

Diener, Edward and Shigehiro Oishi, 2000. “Money and Happiness: Income and Subjective Well-being across Nations,” in Edward Diener and Eunkook M. Suh (eds.), Culture and Subjective Well-being. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press: 185–218.

Dorussen, Han and Hugh Ward, 2010. “Trade Networks and the Kantian Peace,” Journal of Peace Research 47, 1: 29–42.

Doyle, Michael W., 1986. “Liberalism and World Politics,” American PoliticalScience Review 80, 4: 1151–1169.

Easterlin, Richard A., 1974. “Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot?” in P. A. David and M. Reder (eds.), Nations, Households, and Economic Growth. New York: Academic Press, 98–125.

Easterlin, Richard A., 2003. “Explaining Happiness,” Proceedings of theNational Academy of the Sciences 100, 19: 11176–11183.

Easterlin, Richard A., 2005. “Feeding the Illusion of Growth and Happiness: A Reply to Hagerty and Veenhoven,” Social Indicators Research 74, 3: 429–443.

Easterlin, Richard A., 2009. “Lost in Transition: Life Satisfaction on the Road to Capitalism.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 71: 130–145.

Eberstadt, Nicholas, 2016. Men Without Work: America’s Invisible Crisis. Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Press.

Eberstadt, Nicholas, 2017. “Our Miserable 21st Century,” Commentary, February 22, 2017.

Ebstein, Richard P., Olga Novick, Roberto Umansky, Beatrice Priel, Yamima Osher, Darren Blaine, Estelle R. Bennett, Lubov Nemanov, Miri Katz and Robert H. Belmaker, 1996. “Dopamine D4 Receptor (D4DR) Exon III Polymorphism Associated with the Human Personality Trait of Novelty Seeking,” Nature Genetics 12, 1: 78–80.

Eckstein, Harry, 1961. A Theory of Stable Democracy (No. 10). Center of International Studies, Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University.

Ellison, Christopher G., David A. Gay and Thomas A. Glass. 1989. “Does Religious Commitment Contribute to Individual Life Satisfaction?” Social Forces 68, 1: 100–123.

Estes, Richard, 2010. “The World Social Situation: Development Challenges at the Outset of a New Century,” Social Indicators Research 98, 363–402. Euro-Barometer Surveys. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/COMMFrontOffice/publicopinion/index.cfm (accessed October 28, 2017).

European Community Survey. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-community-household-panel (accessed October 28, 2017).

European Value Survey. Available at www.europeanvaluesstudy.eu/ (accessed October 28, 2017).

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2014. “Percent of Employment in Agriculture in the United States.” Available at http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/ series/USAPEMANA (accessed October 28, 2017).

Fincher, Corey L. and Randy Thornhill, 2008. “Assortative Sociality, Limited Dispersal, Infectious Disease and the Genesis of the Global Pattern of Religion Diversity,” Proceedings of the Royal Society 275, 1651: 2587–2594.

Fincher, Corey L., Randy Thornhill, Damian R. Murray and Mark Schaller, 2008. “Pathogen Prevalence Predicts Human Cross-cultural Variability in Individualism/Collectivism,” Proceedings of the Royal Society B 275, 1640: 1279–1285.

Finke, Roger, 1992. “An Unsecular America,” in Steve Bruce (ed.), Religion and Modernization: Sociologists and Historians Debate the Secularization Thesis. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 145–169.

Finke, Roger and Laurence R. Iannaccone, 1993. “The Illusion of Shifting Demand: Supply-side Explanations for Trends and Change in the American Religious Market Place,” Annals of the American Association of Political and Social Science 527: 27–39.

Finke, Roger and Rodney Stark, 2000. Acts of Faith: Explaining the HumanSide of Religion. Berkeley, CA: The University of California Press.

Ford, Martin, 2015. Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a JoblessFuture. New York: Basic Books.

Freedom House, 2014. Freedom in the World. http://freedomhouse.org/article/freedom-world-2014 (accessed October 28, 2017).

Frey, Bruno S. and Alois Stutzer, 2000. “Happiness Prospers in Democracy,” Journal of Happiness Studies 1, 1: 79–102.

Frey, Carl Benedikt and Michael A. Osborne, 2012. The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation. Oxford: Oxford University Programme on the Impacts of Future Technology.

Frydman, Carola and Dirk Jenter. 2010. “CEO Compensation,” AnnualReview of Economics 2, 1: 75–102.

Fujita, Frank and Ed Diener, 2005. “Life Satisfaction Set Point: Stability and Change,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 88, 1: 158–164.

Fukuyama, Francis, 1995. Trust: Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity. New York: Free Press.

Gartzke, Erik, 2007. “The Capitalist Peace,” American Journal of PoliticalScience 51, 1: 166–191.

Gat, Azar, 2005. “The Democratic Peace Theory Reframed: The Impact of Modernity,” World Politics 58, 1: 73–100.

Gat, Azar, 2006. War in Human Civilization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gelfand, Michele J., Jana L. Raver, Lisa Nishii, Lisa M. Leslie, Janetta Lun, Beng Chong Lim, Lili Duan et al., 2011. “Differences between Tight and Loose Cultures: A 33-Nation Study,” Science 332, 6033: 1100–1104. German Election Study. Available at http://gles.eu/wordpress/ (accessed October 28, 2017).

Gilens, Martin, 2012. Affluence and Influence. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Goldstein, Joshua S., 2011. Winning the War on War: The Decline of ArmedConflict Worldwide. New York: Plume.

Goos, Maarten, Alan Manning and Anna Salomons, 2014. “Explaining Job Polarization: Routine-Biased Technological Change and Offshoring,” The American Economic Review 104, 8: 2509–2526.

Greene, Joshua and Jonathan Haidt, 2002. “How (and Where) Does Moral Judgment Work?” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 6, 12: 517–523.

Hacker, Jacob S., 2008. The Great Risk Shift. New York: Oxford University Press. Hacker, Jacob S. and Paul Pierson, 2010. Winner-Take-All Politics. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Hadlock, Paul, Daniel Hecker and Joseph Gannon, 1991. “High Technology Employment: Another View,” Bureau of Labor Statistics Monthly Labor Review: July: 26–30.

Hagerty, Michael R. and Ruut Veenhoven, 2003. “Wealth and Happiness Revisited – Growing National Income Does Go with Greater Happiness,” Social Indicators Research 64, 1: 1–27.

Haidt, Jonathan and Fredrik Bjorklund, 2008, “Social Intuitionists Answer Six Questions about Morality,” Moral Psychology 2: 181–217.

Haller, Max and Markus Hadler, 2004. “Happiness as an Expression of Freedom and Self-determination: A Comparative Multilevel Analysis,” in W. Glatzer, S. von Below and M. Stoffregen (eds.), Challenges for Quality of Life in the Contemporary World. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 207–229.

Hamer, Dean H., 1996. “The Heritability of Happiness,” Nature Genetics 14, 2: 125–126.

Headey, Bruce and Alexander Wearing, 1989. “Personality, Life Events, and Subjective Well-being: Toward a Dynamic Equilibrium Model,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57, 4: 731–739.

Hecker, Daniel E., 2005. “High Technology Employment: A NAICS-based Update,” Bureau of Labor Statistics Monthly Labor Review, July: 57–72.

Hecker, Daniel, 1999. “High Technology Employment: A Broader View,” Bureau of Labor Statistics Monthly Labor Review, June: 18–28.

Hegre, Håvard, John R. Oneal and Bruce Russett, 2010. “Trade Does Promote Peace: New Simultaneous Estimates of the Reciprocal Effects of Trade and Conflict,” Journal of Peace Research 47, 6: 763–774.

Helliwell, John F., 1993. Empirical Linkages between Democracy and Economic Growth. British Journal of Political Science 24: 225–248.

Hibbs, Douglas A. 1977. “Political Parties and Macroeconomic Policy,” American Political Science Review 71, 4: 1467–1487.

Hicks, Michael J. and Srikant Devaraj. 2015. “The Myth and the Reality of Manufacturing in America.” Center for Business and Economic Research, Ball State University.

Hochschild, Arlie Russell, 2016. Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger andMourning on the American Right. New York: The New Press.

Hofstede, Geert, 1980. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences inWork-Related Values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Hofstede, Geert, 2001. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations across Nations. 2nd Edition, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hughes, Barry B. and Evan E. Hillebrand, 2012. Exploring and ShapingInternational Futures. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishing.

Human Development Report, 2013. The Rise of the South: Human Progress in a Diverse World. New York: United Nations Development Programme. Human Security Report Project, 2012. Human Security Report 2012. Vancouver: Human Security Press.

Huntington, Samuel P., 1991. The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late20th Century. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Huntington, Samuel P., 1996. The Clash of Civilizations: Remaking of theWorld Order. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Ignazi, Piero, 1992. “The Silent Counter-revolution,” European Journal ofPolitical Research 22(1), 3–34.

Ignazi, Piero, 2003. Extreme Right Parties in Western Europe. Oxford University Press.

Inglehart, Ronald F., 1971. “The Silent Revolution in Europe: Intergenerational Change in Post-Industrial Societies,” American Political Science Review 65, 4: 991–1017.

Inglehart, Ronald F., 1977. The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, Ronald F., 1984. “The Changing Structure of Political Cleavages in Western Society,” in R. J. Dalton, S. Flanagan and P. A. Beck (eds.), Electoral Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies: Realignment or Dealignment? Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, Ronald F., 1990. Cultural Shift in Advanced Industrial Society. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, Ronald F., 1997. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, Ronald F., 2003. “How Solid is Mass Support for Democracy – and How Do We Measure It?” PS: Political Science and Politics 36, 1: 51–57.

Inglehart, Ronald F., 2008. “Changing Values among Western Publics, 1970–2006: Postmaterialist Values and the Shift from Survival Values to Self-Expression Values,” West European Politics 31, 1–2: 130–146.

Inglehart, Ronald F., 2010. “Faith and Freedom: Traditional and Modern Ways to Happiness,” in Ed Diener, Daniel Kahneman and John Helliwell (eds.), International Differences in Well-being. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 351–397.

Inglehart, Ronald F., 2015. “Insecurity and Xenophobia: Comment on Paradoxes of Liberal Democracy,” Perspectives on Politics 13,2 (June, 2015): 468–470.

Inglehart, Ronald F., 2016 “Inequality and Modernization: Why Equality is likely to Make a Comeback,” Foreign Affairs January–February, 95, 1: 2–10.

Inglehart, Ronald F. and Christian Welzel, 2004. “What Insights Can MultiCountry Surveys Provide about People and Societies?” APSA Comparative Politics Newsletter 15,2 (summer, 2004): 14–18.

Inglehart, Ronald F. and Christian Welzel, 2005. Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Inglehart, Ronald F. and Christian Welzel, 2009. “How Development Leads to Democracy: What We Know About Modernization,” Foreign Affairs March/April: 33–48.

Inglehart, Ronald F. and Christian Welzel, 2010.“Changing Mass Priorities: The Link between Modernization and Democracy,” Perspectives on Politics 8, 2: 551–567.

Inglehart, Ronald F. and Hans-Dieter Klingemann, 2000. “Genes, Culture, Democracy, and Happiness,” in Ed Diener and Eunkook M. Suh (eds.), Culture and Subjective Well–being. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 165–183.

Inglehart, Ronald F. and Pippa Norris, 2004. Rising Tide: Gender Equality inGlobal Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Inglehart, Ronald F. and Pippa Norris, 2016. “Trump, Brexit, and the Rise of Populism: Economic Insecurity and Cultural Backlash.” Paper presented at the meeting of the American Political Science Association. Philadelphia (September).

Inglehart, Ronald F. and Pippa Norris, 2017. “Trump and the Xenophobic Populist Parties: The Silent Revolution in Reverse,” Perspectives on Politics (June) 15 (2): 443–454.

Inglehart, Ronald F. and Wayne E. Baker, 2000. “Modernization and Cultural Change and the Persistence of Traditional Values,” American Sociological Review 65, 1: 19–51.

Inglehart, Ronald F., Bi Puranen and Christian Welzel, 2015. “Declining Willingness to Fight in Wars: The Individual-level component of the Long Peace,” Journal of Peace Research 52, 4: 418–434.

Inglehart, Ronald F., Mansoor Moaddel and Mark Tessler, 2006. “Xenophobia and In-Group Solidarity in Iraq: A Natural Experiment on the Impact of Insecurity,” Perspectives on Politics 4, 3: 495–506.

Inglehart, Ronald F., R. Foa, Christopher Peterson and Christian Welzel, 2008. “Development, Freedom and Rising Happiness: A Global Perspective, 1981–2007,” Perspectives on Psychological Science 3, 4: 264–285.

Inglehart, Ronald F., Ronald C. Inglehart and Eduard Ponarin, 2017. “Cultural Change, Slow and Fast,” Social Forces (January) 1–28.

Inglehart, Ronald F., Svetlana Borinskaya, Anna Cotter, Jaanus Harro, Ronald C. Inglehart, Eduard Ponarin and Christian Welzel, 2014. “Genetic Factors, Cultural Predispositions, Happiness and Gender Equality,” Journal of Research in Gender Studies 4, 1: 40–69.

International Labor Organization. 2012. Laborstat. Available at http://laborsta.ilo.org/ (accessed October 28, 2017).

Iversen, Torben and David Soskice, 2009.“Distribution and Redistribution: The Shadow of the Nineteenth Century,” World Politics 61, 3: 438–486.

Johnson, Wendy and Robert F. Krueger, 2006. “How Money Buys Happiness: Genetic and Environmental Processes Linking Finances and Life Satisfaction,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90, 4: 680–691. Kahneman, Daniel, Alan B. Krueger, David A. Schkade, Norbert Schwarz and Arthur A. Stone, 2004. “A Survey Method for Characterizing Daily Life Experience: The Day Reconstruction Method,” Science 306, 5702: 1776–1780.

Kahneman, Daniel, 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux. Kahneman, Daniel and Alan B. Krueger, 2006. “Developments in the Measurement of Subjective Well-being,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 20, 1: 3–24.

Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay and Massimo Mastruzzi. 2003. “Government Matters III: Governance Indicators for 1996–2002.” No. 3106. The World Bank.

Kehm, Barbara M., 1999. Higher Education in Germany: Developments, Problems Perspectives. Bucharest: UNESCO European Centre for Higher Education.

Kenny, Charles, 2005. “Does Development Make You Happy? Subjective Wellbeing and Economic Growth in Developing Countries,” Social Indicators Research 73, 2: 199–219.

Kitschelt, Herbert with Anthony J. McGann, 1995. The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Koopmans, Ruud, Paul Statham, Marco Giugni and Florence Passy, 2005. Contested Citizenship. Political Contention over Migration and Ethnic Relations in Western Europe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Krueger, Alan B., 2016. “Where Have All the Workers Gone?” National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) October 4.

Kutscher, Ronald E. and Jerome Mark, 1983. “The Service-producing Sector: Some Common Perceptions Reviewed,” Monthly Labor Review 21–24.

Larsen, Randy J., 2000. “Toward a Science of Mood Regulation,” PsychologicalInquiry 11, 3: 129–141.

Lebergott, Stanley, 1966. “Labor Force and Employment, 1800–1960,” in Dorothy S. Brady (ed.), Output, Employment, and Productivity in the United States after 1800. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research: 117–204.

Lenski, Gerhard E., 1966. Power and Privilege: A Theory of Social Stratification, Englewood Cliffs: McGraw-Hill.

Lerner, Daniel, 1958. The Passing of Traditional Society: Modernizing theMiddle East. New York: Free Press.

Lesthaeghe, Ron and Johan Surkyn, 1988. “Cultural Dynamics and Economic Theories of Fertility Change,” Population and Development Review, 141: 1–46.

Lewis-Beck, Michael S., 2005. “Election Forecasting: Principles and Practice,” British Journal of Politics and International Relations 7: 145–164.

Lim, Chaeyoon and Robert D. Putnam, 2010. “Religion, Social Networks, and Life Satisfaction,” American Sociological Review 75: 914–933.

Lipset, Seymour Martin, 1959.“Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy,” American Political Science Review 53, 1: 69–105.

Lipset, Seymour Martin, 1960. Political Man. Garden City, New York: Anchor Books.

Lucas, Richard E., Andrew E. Clark, Yannis Georgellis and Ed Diener, 2005. “Reexamining Adaptation and the Set Point Model of Happiness: Reactions to Changes in Marital Status,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 84, 3: 527–539.

Lykken, David and Auke Tellegen, 1996. “Happiness Is a Stochastic Phenomenon,” Psychological Science 7, 3: 186–189.

Lyubomirsky, Sonja, Kennon M. Sheldon and David Schkade, 2005. “Pursuing Happiness: The Architecture of Sustainable Change,” Review of General Psychology 9, 2: 111–131.

Maddison, Angus, 2001. The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective. Paris: Development Centre Studies, OECD.

Markoff, John and Amy White. 2009. “The Global Wave of Democratization,” in Christian W. Haerpfer, Patrick Bernhagen, Ronald F. Inglehart and Christian Welzel (eds.), Democratization. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 55–73.

Marks, Gary, Liesbet Hooghe, Moira Nelson and Erica Edwards, 2006. “Party Competition and European Integration in the East and West: Different Structure, Same Causality,” Comparative Political Studies 39, 2: 155–175.

Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels, 1848. The Communist Manifesto. London: The Communist League.

McAfee, Andrew, 2017. A FAQ on Tech, Jobs and Wages. https://futureoflife.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Andrew-McAfee.pdf (accessed October 29, 2017).

McDonald, Patrick J., 2009. The Invisible Hand of Peace: Capitalism, the War Machine, and International Relations Theory. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Meyer-Schwarzenberger, Matthias, 2014. “Individualism, Subjectivism, and Social Capital: Evidence from Language Structures.” Paper presented at summer workshop of Laboratory for Comparative Social Research, Higher School of Economics, St. Petersburg, Russia, June 29–July 12, 2014.

Milanovic, Branko, 2016. Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age ofGlobalization. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Milbrath, Lester W. and Madan Lal Goel, 1977. Political Participation: How and Why Do People Get Involved in Politics? Boston: Rand McNally College Publishing Co.

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology – Japan, 2012. “Statistics.” Available at www.mext.go.jp/english/statistics/index.htm (accessed October 29, 2017).

Minkov, Michael and Michael Harris Bond, 2016. “A Genetic Component to National Differences in Happiness,” Journal of Happiness Studies 1–20.

Mishel, Lawrence and Natalie Sabadish, 2013. “CEO Pay in 2012 Was Extraordinarily High Relative to Typical Workers and Other High Earners,” Economic Policy Institute Issue Brief #367. Available at www.epi.org/publication/ceo-pay-2012-extraordinarily-high/ (accessed October 29, 2017).

Møller, Jørgen and Svend-Erik Skaaning, 2013. “The Third Wave: Inside the Numbers,” Journal of Democracy 24, 4: 97–109.

Moore, Barrington, 1966. The Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. Boston: Beacon Press.

Morewedge, Carey K. and Daniel Kahneman, 2010. “Associative Processes in Intuitive Judgment,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 14: 435–440.

Morris, Ian, 2015. Foragers, Farmers and Fossil Fuels: How Human ValuesEvolve. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Mousseau, Michael, Håvard Hegre and John R. O’neal, 2003. “How the Wealth of Nations Conditions the Liberal Peace,” European Journal of International Relations 9, 2: 277–314.

Mousseau, Michael, 2009. “The Social Market Roots of Democratic Peace,” International Security 33, 4: 52–86.

Mudde, Cas, 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press, Chapter 4.

Mueller, John, 1989. Retreat from Doomsday: The Obsolescence of MajorWar. New York: Basic Books.

Muller, Edward N., 1988. “Democracy, Economic Development, and Income Inequality,” American Sociological Review 53: 50–68.

National Center for Education Statistics, 2014. Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. Available at http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/ (accessed October 29, 2017).

National Center of Education Statistics, 2012. Digest of Education Statistics. National Science Board, 2012. Science and Engineering Indicators 2012. Arlington, VA: National Science Foundations (NSB 12-01).

National Science Board, 2014. Science and Engineering Indicators 2014. Arlington, VA: National Science Foundations (NSB 14-01).

NCHS Data Brief No. 267 December 2016. US Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics Mortality in the United States, 2015. Jiaquan Xu, M.D., Sherry L. Murphy, B.S., Kenneth D. Kochanek, M.A., and Elizabeth Arias, Ph.D.

Niedermayer, Oskar, 1990. “Sozialstruktur, politische Orientierungen und die Uterstutzung extrem rechter Parteien in Westeuropa,” Zeitschrift fur Parlamentsfragen 21, 4: 564–582.

Nolan, Patrick and Gerhard Lenski, 2015. Human Societies: An Introduction to Macrosociology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Norris, Pippa, 2007. Radical Right. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Norris, Pippa and Ronald F. Inglehart, 2011. Sacred and Secular: Religionand Politics Worldwide (2nd edn.). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Norris, Pippa and Ronald F. Inglehart, 2009. Cosmopolitan Communications: Cultural Diversity in a Globalized World. New York: Cambridge University Press.

North, Douglass C. and Barry R. Weingast, 1989. “Constitutions and Commitment: The Evolution of Institutions Governing Public Choice in Seventeenth Century England,” Journal of Economic History 49, 4: 803–832.

OECD, 2014. OECD Factbook Statistics. OECD iLibrary.

Oneal, John R. and Bruce M. Russet, 1997. “The Classical Liberals Were Right,” International Studies Quarterly 41, 2: 267–293.

Ott, Jan, 2001. “Did the Market Depress Happiness in the US?” Journal ofHappiness Studies 2, 4: 433–443.

Oyserman, Daphna, Heather M. Coon and Markus Kemmelmeier, 2002. “Rethinking Individualism and Collectivism: Evaluation of Theoretical Assumptions and meta-analyses,” Psychological Bulletin 128: 3–72.

Page, Benjamin I., Larry M. Bartels and Jason Seawright, 2013. “Democracy and the Policy Preferences of Wealthy Americans,” Perspectives on Politics 11, 1: 51–73.

Pegram, Thomas, 2010. “Diffusion across Political Systems: The Global Spread of National Human Rights Institutions,” Human Rights Quarterly 32, 3: 729–760.

Penn World Tables. http://cid.econ.ucdavis.edu/pwt.html (accessed October 29, 2017).

Piketty, Thomas, 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Pinker, Steven, 2011. The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence HasDeclined. New York: Viking Press.

Politbarometer, 2012. Available at: www.forschungsgruppe.de/Umfragen/ Politbarometer/Archiv/Politbarometer_2012/ (accessed October 29, 2017).

Powell, Walter W. and Kaisa Snellman, 2004. “The Knowledge Economy,” Annual Review of Sociology 30: 199–220.

Prentice, Thomson, 2006. “Health, History and Hard Choices: Funding Dilemmas in a Fast-Changing World,” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 37, 1: 63S–75S.

Przeworski, Adam and Fernando Limongi, 1997. “Modernization: Theories and Facts,” World Politics 49, 2: 155–183.

Puranen, Bi, 2008. How Values Transform Military Culture – The SwedishExample. Stockholm: Sweden: Values Research Institute.

Puranen, Bi, 2009. “European Values on Security and Defence: An Exploration of the Correlates of Willingness to Fight for One’s Country,” in Y. Esmer, H. D. Klingemann and Bi Puranen (eds.), Religion, Democratic Values and Political Conflict. Uppsala: Uppsala University: 277–304.

Putnam, Robert D., 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions inModern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Raleigh, Donald, 2006. Russia’s Sputnik Generation: Soviet Baby BoomersTalk about Their Lives. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Ridley, Matt, 1996. The Origins of Virtue: Human Instincts and the Evolutionof Cooperation. London: Penguin Press Science.

Ridley, Matt, 2011. The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves. New York: Harper Perennial.

Rifkin, Jeremy, 2014. The Zero Marginal Cost Society: The Internet of Things, the Collaborative Commons and the Eclipse of Capitalism. New York: Palgrave, Macmillan.

Robinson, William, 1950. Ecological Correlations and the Behavior of Individuals. American Sociological Review 15, 3: 351–357.

Rokeach, Milton, 1960. The Open and Closed Mind. New York: Basic Books.

Rokeach, Milton, 1968. Beliefs, Attitudes and Values. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, Inc.

Rosecrance, Richard, 1986. The Rise of the Trading State: Commerce andConquest in the Modern World. New York: Basic Books.

Rothstein, Bo, 2017. “Why Has the White Working Class Abandoned the Left?” Social Europe, January 19. Available at www.socialeurope.eu/2017/01/white-working-class-abandoned-left/ (accessed October 29, 2017).

Saez, Emmanuel and Gabriel Zucman, 2014. “Wealth Inequality in the U.S. since 1913: Evidence from Capitalized Income Tax Data,” NBER working paper No. 20625. Available at www.nber.org/papers/w20625 (accessed October 29, 2017).

Sanfey, Alan G., James K. Rilling, Jessica A. Aronson, Leigh E. Nystrom and Jonathan D. Cohen, 2003. “The Neural Basis of Economic Decisionmaking in the Ultimatum Game,” Science 300, 5626: 1755–1758.

Schock, Kurt, 2013. “The Practice and Study of Civil Resistance,” Journal ofPeace Research 50, 3: 277–290.

Schwartz, Shalom, 2006. “A Theory of Cultural Value Orientations: Explication and Applications,” Comparative Sociology 5, 2–3: 137–182.

Schwartz, Shalom, 2013. “Value Priorities and Behavior: Applying,” ThePsychology of Values: The Ontario Symposium. Vol. 8.

Schyns, Peggy, 1998. “Cross-national Differences in Happiness: Economic and Cultural Factors Explored,” Social Indicators Research 42, 1/2: 3–26.

Selig, James P., Kristopher J. Preacher and Todd D. Little, 2012. “Modeling Time-Dependent Association in Longitudinal Data: A Lag as Moderator Approach,” Multivariate Behavioral Research 47, 5: 697–716.

Sen, Amartya, 2001. Development as Freedom. New York: Alfred Knopf.

Shcherbak, Andrey, 2014. “Does Milk Matter? Genetic Adaptation to Environment: The Effect of Lactase Persistence on Cultural Change.” Paper presented at summer workshop of Laboratory for Comparative Social Research, Higher School of Economics, St. Petersburg, Russia, June 29–July 12, 2014.

Sides, John and Jack Citrin, 2007. “European Opinion about Immigration: The Role of Identities, Interests and Information,” British Journal of Political Science 37, no. 03: 477–504.

Silver, Nate, 2015. The Signal and the Noise. New York: Penguin.

Singh, Gopal K. and Peter C. van Dyck, 2010. Infant Mortality in the United States, 1935–2007. Rockville, Maryland: US Department of Health and Human Services.

Sniderman, Paul M., Michael Bang Petersen, Rune Slothuus and Rune Stubager, 2014. Paradoxes of Liberal Democracy: Islam, Western Europe, and theDanish Cartoon Crisis. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Snyder, Thomas D. (ed.), 1993. 120 Years of American Education: A StatisticalPortrait. Washington, DC: US Department of Education.

Soon, Chun Siong, Marcel Brass, Hans-Jochen Heinze and John-Dylan Haynes, 2008. “Unconscious Determinants of Free Decisions in the Human Brain,” Nature Neuroscience 11, 5: 543–545.

Stark, Rodney and William Sims Bainbridge, 1985a. “A Supply-side Reinterpretation of the ‘Secularization’ of Europe,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 33, 3: 230–252.

Stark, Rodney and William Sims Bainbridge, 1985b. The Future of Religion: Secularization, Revival, and Cult Formation. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Statistisches Bundesamt, 2012. “Education, Research, and Culture Statistics.” Available at www.destatis.de/EN/FactsFigures/InFocus/ EducationResearchCulture/VocationalTraining.html (accessed November 18, 2017).

Stenner, Karen, 2005. The Authoritarian Dynamic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stiglitz, Joseph E., 2011. “Of the 1 Percent, by the 1 Percent, for the 1 Percent,” Vanity Fair, May.

Stiglitz, Joseph E., 2013. The Price of Inequality. New York: Norton.

Sweet, Ken, 2014. “Median CEO Pay Crosses $10 Million in 2013,” AssociatedPress, May 27, The American National Election Studies (ANES; www.electionstudies.org).

Thomas, Scott M., 2007. “Outwitting the Developed Countries? Existential Insecurity and the Global Resurgence of Religion,” Journal of International Affairs 61, 1: 21.

Thomas, Scott M., 2005. The Global Resurgence of Religion and the Transformation of International Relations: The Struggle for the Soul of the Twenty-first Century. New York: Palgrave, Macmillan.

Thompson, Mark R., 2000. “The Survival of ’Asian Values’ as ‘Zivilisationskritik.’” Theory and Society 29, no. 5: 651–686.

Thornhill, Randy, Corey L. Fincher and Devaraj Aran, 2009. “Parasites, Democratization, and the Liberalization of Values across Contemporary Countries,” Biological Reviews 84, 1: 113–131.

Thornhill, Randy, Corey L. Fincher, Damian R. Murray and Mark Schaller, 2010. “Zoonotic and Non-zoonotic Diseases in Relation to Human Personality and Societal Values,” Evolutionary Psychology 8:151–155.

Toffler, Alvin, 1990. Powershift: Knowledge, Wealth, Violence in the 21stCentury. New York: Bantam.

Traugott, Michael, 2001. “Trends: Assessing Poll Performance in the 2000 Campaign,” Public Opinion Quarterly 65, 3: 389–419.

Tversky, Amos and Daniel Kahneman, 1974. “Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases,” Science 185, 4157: 1124–1131.

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2012. World PopulationProspectus: The 2012 Revision.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2012. World Population Prospectus: The 2012 Revision. http://esa.un.org/wpp/ (accessed October 29, 2017).

United Nations Population Division – Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2016.

United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2013. “International Comparisons of Annual Labor Force Statistics, 1970–2012.” Available at: www.bls.gov/fls/ flscomparelf.htm (accessed October 29, 2017).

United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014. www.bls.gov/ (accessed October 29, 2017).

United States Bureau of the Census, 1977. Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce.

United States Census Bureau, 2012. Statistical Abstract of the United States. United States Census Bureau, 2014. “Historical Income Tables: People.” Available at www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/incomepoverty/historical-income-people.html (accessed October 29, 2017).

Van de Kaa, Dirk J., 2001. “Postmodern Family Preferences: From Changing Value Orientation to New Behavior,” Population and Development Review 27: 290–331.

Van der Brug, Wouter, Meindert Fennema and Jean Tillie, 2005. “Why Some Anti-Immigrant Parties Fail and Others Succeed: A Two-Step Model of Aggregate Electoral Support,” Comparative Political Studies 38, 537–573.

Vanhanen, Tatu, 2003. Democratization: A Comparative Analysis of 170Countries. New York: Routledge.

Veenhoven, Ruut, 2014. World Database of Happiness, Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands. http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl (accessed October 29, 2017).

Veenhoven, Ruut, 2000. “Freedom and Happiness: A Comparative Study in Forty-four Nations in the Early 1990s,” in Ed Diener and Eunkook M. Suh (eds.), Culture and Subjective Well Being. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 257–288.

Verba, Sidney, Norman H. Nie and Jae-on Kim, 1978. Participation and Political Equality: A Seven-Nation Comparison. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Weber, Max, 1904 [1930]. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. London: Routledge.

Welsch, Heinz, 2003. “Freedom and Rationality as Predictors of Cross-national Happiness Patterns: The Role of Income as a Mediating Value,” Journal of Happiness Studies 4, 3: 295–321.

Welzel, Christian, 2007. “Are Levels of Democracy Affected by Mass Attitudes? Testing Attainment and Sustainment Effects on Democracy,” InternationalPolitical Science Review 28, 4: 397–424.

Welzel, Christian, 2013. Freedom Rising: Human Empowerment and theQuest for Emancipation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Welzel, Christian and Ronald F. Inglehart, 2008. “The Role of Ordinary People in Democratization,” Journal of Democracy 19, 1: 126–140.

Whyte, Martin K., 2014. “Soaring Income Gaps: China in Comparative Perspective,” Daedalus 143, 2: 39–52.

Williams, Donald E. and J. Kevin Thompson, 1993. “Biology and Behavior: A Set-point Hypothesis of Psychological Functioning,” Behavior Modification 17, 1: 43–57.

Wilson, Timothy, 2002. Strangers to Ourselves: Discovering the AdaptiveUnconscious. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Winters, Jeffrey A., 2011.Oligarchy. New York, Cambridge University Press.

Winters, Jeffrey A. and Benjamin I. Page, 2009. “Oligarchy in the United States?” Perspectives on Politics 7, 4:731–751.

Wiseman, Paul, 2013. “Richest One Percent Earn Biggest Share since ’20s,”AP News, September 10.

Wolfers, Justin, 2015. “All You Need to Know about Income Inequality, in One Comparison,” New York Times, March 13.

World Bank, 2012. World Development Indicators. Available at http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators (accessed October 29, 2017).

World Bank Databank, 2015. “GINI Index.” Available at http://data.world bank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI/ (accessed October 29, 2017).

World Values Surveys, 2014. Available at www.worldvaluessurvey.org/ (accessed October 29, 2017).

www.forschungsgruppe.de/Umfragen/Politbarometer/Archiv/Politbarometer_2012/ (accessed October 29, 2017).

www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates15.shtml (accessed October 29, 2017).

www.destatis.de/EN/FactsFigures/SocietyState/SocietyState.html (accessed October 29, 2017).

Zakaria, Fareed and Lee Kuan Yew, 1994. “Culture Is

Destiny: A Conversation with Lee Kuan Yew,” Foreign Affairs: 109–126.

Zakharov, Alexei. 2016. “The Importance of Economic Issues in Politics: A Cross-Country Analysi

s.” Paper presented at Higher School of Economics, Moscow, November 8–10.

INDEX

an lạc chủ quan, sự, (subjective well-being) 32, 39, 142, 167–71

các chỉ báo về sự an lạc chủ quan, 146, 150

các mức an lạc chủ quan tăng lên, 147

các số đo về an lạc chủ quan, 145, 160

sự giảm sút an lạc chủ quan, 158, 163

sự phát triển kinh tế và sự an lạc chủ quan, 147, 150

sự tăng an lạc chủ quan, 143

an toàn tồn tại (existential security)

sự giảm sút an toàn tồn tại, 32, 58, 173

index an toàn tồn tại, 88, 91, 110

mức an toàn tồn tại cao, 5, 9, 23, 30, 79, 89, 93

cảm giác về sự an toàn tồn tại, 15, 19, 62, 124

B

bất an kinh tế, sự (economic insecurity) 15, 185, 199

bất bình đẳng

bất bình đẳng kinh tế, 68, 137, 161, 192, 210

bất bình đẳng tăng lên, 84, 171, 175, 186, 193, 196, 212

bất bình đẳng thu nhập, 87, 154, 193

index bất bình đẳng Gini, 70, 193, 215

bầu cử Tổng thống Mỹ

các cuộc bầu cử Tổng thống Mỹ 2004, 96

các cuộc bầu cử Tổng thống Mỹ 2016, 191

các cuộc bầu cử sơ bộ Tổng thống Mỹ 2016, 210

biết dọc biết viết hàng loạt, sự, (mass literacy), 9, 116, 131, 197

bình đẳng giới (gender equality), 1, 9, 16, 187

bình đẳng giới tăng lên, 11, 102, 143, 147

chống bình đẳng giới, 169

sự ủng hộ cho sự bình đẳng giới, 81, 145, 154

bỏ phiếu giai cấp xã hội (social class voting), 175, 189

Brexit, 173

Buffet, Warren, 211

C

can thiệp chính phủ, sự, 209, 214

chế độ độc đoán, 33, 121, 124, 135, 139

Chiến tranh Thế giới I, 115, 193

Chiến tranh Thế giới II, 1–2, 9, 16, 56, 63, 79, 104–5, 107–10, 115, 157, 193, 206

chủ nghĩa cá nhân, 50, 55

Chủ nghĩa dân tộc, 11, 58, 70, 159

Chủ nghĩa hậu-duy vật (postmaterialism), 92, 175

phản ứng dữ dội chống lại chủ nghĩa hậu-duy vật, 180

chủ nghĩa Tập thể, 2, 50–52, 55

chuẩn mực lựa chọn-cá nhân (individual-choice norm), 78, 85, 87, 98, 110

các thành phần của chuẩn mực lựa chọn-cá nhân, 108

sự thay đổi sang chuẩn mực lựa chọn-cá nhân, 84, 99, 102

sự ủng hộ cho chuẩn mực lựa chọn-cá nhân, 89, 93, 94, 99

chuẩn mực ủng hộ sinh sản (pro-fertility norm), 78, 83, 89, 100

một sự thay đổi từ các chuẩn mực ủng hộ-sinh sản sang các chuẩn mực lựa chọn-Cá nhân, 78, 80, 100

Clinton, Hilary, 101, 181, 191, 210

công nghiệp hóa, 9, 37, 43, 48, 64, 75, b115, 131, 138

công nghiệp hóa ban đầu, 116, 197

D

dân chủ hóa, 9, 77, 116, 134, 136, 143, 168, 169, 176

làn sóng dân chủ hóa, 3, 34, 124, 126, 128, 129, 137, 152

Dân chủ Xã hội (đảng, những người), 179, 192

dân chủ, 39, 44, 104, 105, 120, 135, 136

chuyển đổi sang dân chủ, 114, 123, 139

dân chủ bầu cử , 118

dân chủ đại diện, 116, 118, 130

dân chủ độc đoán, 118

dân chủ hiệu quả, 34, 118, 119, 121, 123, 126, 130, 138

dân chủ lai, 118

dân chủ tự do (liberal), 121, 123, 130

phát triển kinh tế và dân chủ, 53, 116, 136

sự lan ra của dân chủ, 2, 17, 63, 115, 137, 147, 173, 175, 214

sự nổi lên của dân chủ, 13, 117

Đ

đa dạng sắc tộc (ethnic diversity), 167, 179

đa dạng xã hội, sự, tính, (social diversity), 167

đa số-Muslim, các nước, 18, 33, 46, 75, 166, xem cả các nước theo tên

Đại Suy thoái (Great Recession), 155, 186, 198

Đảng Cộng hòa, 173, 210

Đảng Dân chủ, 210

đảng dân túy bài ngoại, các, 176, 212

đảng độc đoán bài ngoại, các, 174, 178, 179, 181

Đảng Mặt trận Quốc gia (National Front) của Pháp, 5, 173, 183

Đảng Republikaner xem Republikaner

Đảng Xanh, 178

định hướng tình dục, 17, 68, 80, 81, 101, 175

đô thị hóa, 9, 11, 13, 37, 48, 60, 115, 116, 131, 197

đồng tính dục, 17, 41, 77, 82, 89, 169

không chấp nhận sự đồng tính dục, 98

khoan dung với sự đồng tính dục, 13, 40, 80, 83

Đường con con voi (elephant curve), 194

E

elite (giới tinh hoa),

elite cộng sản 10

tính liêm chính elite, 121

European Values Study, 5

F

Freedom House, 118, 121

G

Gates, Bill, 103, 201, 211

GDP trên đầu người, 34, 49, 57, 85, 89, 94, 148

giả thuyết hòa nhập xã hội (socialization hypothesis), 14, 15

giả thuyết khan hiếm, 14–15

Giá trị Á châu, các, 122

giá trị hậu-Duy vật, 26, 88, 93

các giá trị Duy vật/ hậu-Duy vật, 72, 93, 184

một sự thay đổi từ các giá trị Duy vật sang hậu-Duy vật, 1, 14, 22, 29, 36, 72, 77, 88, 95, 183

giá trị linh thiêng vs. thế tục, các, 47

giá trị sinh tồn, các (survival values), 2, 16, 19, 37, 40, 58, 126, 149

sự thay đổi từ các giá trị Sinh tồn sang các giá trị Tự-thể hiện 1, 4, 12, 37, 39, 47, 135, 144, 171

giá trị sinh tồn/tự-thể hiện, các, 37, 44, 47, 49, 52

giá trị thế tục-duy lý, 69

giá trị thế tục-duy lý, các, 18–19, 36–37, 43–44

giá trị tự-thể hiện value, 13, 16, 19, 23, 49, 55, 56, 83, 107, 117, 119–37, 145, 181

giấc mơ Mỹ, 211, 254

giai cấp lao động, 5, 9, 179, 188, 196, 201, 209, 215; giai cấp lao động da trắng, 191, 212

giai cấp trung lưu (middle class), 5, 117, 133, 179, 188, 201, 207

nếp khoái lạc (hedonic treadmill), 141, 169

H

hài lòng với cuộc sống, sự (life satisfaction), 4, 39, 50, 141–45, 161–66

hành động quả quyết (affirmative action) để nâng đỡ những người yếu thế, 179, 211

hạnh phúc, 39, 140, 214

hạnh phúc tăng lên, 152, 166

tối đa hóa hạnh phúc, 140, 149

hệ thống niềm tin, 19, 42, 76, 151, 159, 171

hòa bình dân chủ, 103, 112

hôn nhân đồng giới, 3, 20, 78, 81, 96, 98, 191, 210

hợp pháp hóa hôn nhân đồng giới, 9, 77, 80, 97

huy động nhận thức, 115, 119, 125, 130, 134, 197

kẻ-thắng-ăn-cả (winner-take-all)

nền kinh tế kẻ-thắng-ăn-cả, 175, 193, 198, 201, 212, 214

xã hội kẻ-thắng-ăn-cả, 4, 200

khoan dung, sự, với tính đa dạng ( tolerance of diversity), 37, 39, 157, 167

L

Liên Âu (EU, European Union), 31, 70, 162, 173, 185

liên minh chính trị, 209, 215, 216

Liên Xô (Soviet Union), 32, 71, 111, 158, 159, 160, 162

sự sụp đổ của Liên Xô, 19, 115, 158, 161, 197

ly dị, 17, 36, 40, 68, 78, 84–88

lý thuyết hiện đại hóa cổ điển, 11, 18, 37, 40, 43

lý thuyết hiện đại hóa tiến hóa (evolutionary modernization theory), 8, 13, 30, 47, 55, 63, 83, 136, 152, 167

lý thuyết lựa chọn duy lý, các, (rational choice theories), 19–21

M

Marx, Karl, 10, 42, 60, 61, 116

hệ thống niềm tin Marist, 32, 71, 159, 160

ý thức hệ Marxist, 159

mô hình so sánh xã hội (social comparison model), 169

Mỹ-Latin, các nước, 33, 45, 150, 172, xem cả các nước theo tên

N

National Front xemĐảng Mặt trận Dân tộc

NATO, 70, 71, 111

Nazi, bọn, 177, 186

nền dân chủ Tây phương, các, 3, 18, 118, 122, 126, 189

nền kinh tế công nghiệp, 75

New Deal, 210

nữ hóa xã hội (feminization of society), 102

nước nguyên-cộng sản, các, 31, 32, 58, 70, 95, 150, 160, 219

nước theo tên, các

Ấn Độ (India), 4, 12, 30, 105, 150, 157, 194, 205

Argentina, 32, 54, 157

Australia (Úc), 1, 47, 54, 68

Austria (Áo), 71, 179

Azerbaijan, 34, 71, 120, 163

Ba Lan (Poland), 157

Bangladesh, 34, 150

Belgium (Bỉ), 26

Brazil, 32

Burkina Faso, 150

Canada, 47, 54, 68, 194, 203

Chile, 32, 122, 139

Colombia, 32

Đại Anh (nước Anh) (Great Britain), 26, 47, 68, 176

Đan Mạch (Denmark), 157, 179

Đức (Germany), 108, 203

Guatemala, 32

Hà Lan (Netherlands), 26, 157, 179

Hàn Quốc (South Korea), 122, 139

Hoa Kỳ (United States), 61, 68, 139, 142, 191

Indonesia, 33, 47, 194

Iran, 34, 123

Italy, 108, 111, 157, 179

Kazakhstan, 34

Kyrgyzstan, 34

Lebanon, 34, 106

Luxembourg, 157

Malaysia, 34

Mali, 34, 150

Mexico, 30, 32, 157

Morocco, 33, 47

Na Uy (Norway), 109, 158

Nam Phi (South Africa), 157

New Zealand, 47, 68, 82

Nga (Russia), 30–32, 57–58, 71, 114–15, 158–66

Nhật Bản (Japan), 11, 57, 82, 108, 122, 132, 157

Nigeria, 150

Pakistan, 30, 34

Peru, 32, 129

Phần Lan (Finland), 109, 157

Pháp (France), 26, 68, 111, 146, 157, 179, 203

Qatar, 34, 108

Saudi Arabia, 34

Tây Ban Nha (Spain), 157

Tây Đức (West Germany), 26

Thổ Nhĩ Kỳ (Turkey), 33, 108, 123, 146

Thụy Điển (Sweden), 68, 109, 158, 179, 203

Thụy Sĩ (Switzerland), 158, 179

Trung Quốc, 30, 57, 70, 108, 115, 121, 129, 139, 165, 194

Uganda, 150

Uruguay, 33, 54, 122

Uzbekistan, 34

Việt Nam , 108, 121, 151, 161, 194, 195

Vương quốc Anh, UK, (United Kingdom), 203

Yemen, 34

O

Outsourcing (thuê ngoài), 4, 195, 203

P

phá thai, 17, 36, 68, 78, 79, 82, 84–85, 87, 191

phân cực (polarization), 34, 37

phân cực chính trị, 176, 189

phân cực dựa vào giá trị, 191

phân cực dựa vào giai cấp, 191

phân tích nhóm sinh, 25, 27, 72, 183

phản ứng văn hóa dữ dội (cultural backlash), 174, 176, 185

Phản xạ Độc đoán, 1, 138, 173, 174, 185, 187

Phổ giáo dục, 201

phong trào dân túy độc đoán bài ngoại, 5, 173, 174

phụ thuộc-con đường (path-dependency), 24, 58, 135

Polity IV, 147

Q

quyền tự do biểu đạt (freedom of expression), 12, 16, 117, 129, 143, 174

R

Reagan, Ronald, 192

Reagan-Thatcher, thời đại, xem cả Reagan, Ronald; Thatcher, Margaret

Republikaner, 177, 178, 183

Romney, Mitt, 198

S

sẵn sàng chiến đấu vì tổ quốc mình, 105–13

siêu-chiều tự-thể hiện/chủ nghĩa cá nhân/tự trị, 52, 54, 59

Silent Revolution, 14, 173–79, 214

sụp đổ của chủ nghĩa cộng sản, sự, 32, 56, 152, 158, 163, 170, 193

T

tầng lớp trung lưu xem giai cấp trung lưu

Thatcher, Margaret, 192

thay đổi giá trị giữa thế hệ, sự, 15, 25, 55, 80, 95, 100

quá trình thay đổi giá trị giữa thế hệ, 3, 12, 20, 124, 128

thay đổi văn hóa giữa thế hệ, sự, 1

thay thế dân cư giữa thế hệ, sự, 14–16, 21–23, 29, 72, 77–80, 84, 91, 94, 95, 183

thế tục hóa, 2, 37, 60, 67–69, 75–76

thuê ngoài xem outsourcing

tiến hóa văn hóa, sự 39, 106, 113, 171

tính bài ngoại (xenophobia), 8–9, 13, 100, 138, 174, 179, 185–86

tính sùng đạo (religiosity), 58, 61, 69, 92, 152, 159, 165, 169

toàn cầu hóa, 4, 42, 48, 58, 63, 103, 198

Trump, Donald, 100, 181, 191, 198, 210

tự do hóa xã hội (social liberalization), 168, 169, 172

tự do lựa chọn (freedom of choice), 3, 39, 121, 124, 144, 152, 166, 214

tự động hóa, 4, 195, 203, 215

tuổi thọ kỳ vọng xemước lượng tuổi thọ

tỷ lệ sinh sản (fertility rate), 2, 69, 70, 82, 87

tỷ lệ sinh sản cao, 68, 77, 81

tỷ lệ sinh sản giảm, 42, 69, 75

tỷ lệ tử vong trẻ sơ sinh (infant mortality), 34, 78, 81, 83, 94, 100

Ư

ước lượng tuổi thọ (life expectancy), 10, 89, 91, 143

các số đo của ước lượng tuổi thọ, 92

ước lượng tuổi thọ đàn ông, 32, 58, 161

ước lượng tuổi thọ tăng lên, 11, 100, 115, 197

ước lượng tuổi thọ trung bình, 49, 146

ước lượng tuổi thọ trung vị, 34

W

World Bank, 71, 86, 119, 147

World Values Survey, 5, 146, 187

X

xã hội nông nghiệp, 3, 12, 37, 62, 81, 140

xã hội tri thức, 65, 75, 103, 134, 193, 200–3

Xã hội Trí tuệ Nhân tạo, 4, 171, 175, 195, 200, 201, 214

Xúc cảm (emotion), 20, 21

sự an-lạc xúc cảm (emot

ional

Rona

ng), 206

sự ủ hộ tình cảm, 21

Z

Zuckerberg, rk, 201 thế hệ,

sự, 1 1 thay thế dân cư giữa thế hệ, sự, 14–16, 21–23, 29, 72, 77–80, 84, 91, 94, 95, 183 3 thế tục hóa, 2, 37, 60, 67–69, 75–76 6 thuê ngoài xem outsourcingngtiến hóa văn hóa, sự 39, 106, 113, 17171tính bài ngoại (xenophobia), 8–9, 13, 100, 138, 174, 179, 185–8686tính sùng đạo (religiosity), 58, 61, 69, 92, 152, 159, 165, 16969toàn cầu hóa, 4, 42, 48, 58, 63, 103, 198 8 Trump, Donald, 100, 181, 191, 198, 21010tự do hóa xã hội (social liberalization), 168, 169, 17272tự do lựa chọn (freedom of choice), 3, 39, 121, 124, 144, 152, 166, 21414tự động hóa, 4, 195, 203, 21515tuổi thọ kỳ vọng xem ước lượng tuổi thọhọtỷ lệ sinh sản (fertility rate), 2, 69, 70, 82, 8787tỷ lệ sinh sản cao, 68, 77, 8181tỷ lệ sinh sản giảm, 42, 69, 75 5 tỷ lệ tử vong trẻ sơ sinh (infant mortality), 34, 78, 81, 83, 94, 100 0 ƯƯước lượng tuổi thọ (life expectancy), 10, 89, 91, 14343các số đo của ước lượng tuổi thọ, 92 2 ước lượng tuổi thọ đàn ông, 32, 58, 161 1 ước lượng tuổi thọ tăng lên, 11, 100, 115, 19797ước lượng tuổi thọ trung bình, 49, 146 6 ước lượng tuổi thọ trung vị, 3434WWWorld Bank, 71, 86, 119, 14747World Values Survey, 5, 146, 18787XXxã hội nông nghiệp, 3, 12, 37, 62, 81, 14040xã hội tri thức, 65, 75, 103, 134, 193, 200–3–3Xã hội Trí tuệ Nhân tạo, 4, 171, 175, 195, 200, 201, 21414Xúc cảm (emotion), 20, 2121sự an-lạc xúc cảm (emotional well-being), 20606sự ủng hộ tình cảm, 2121ZZZuckerberg, Mark, 2010

L