Tino Cao

* See French and English versions below.

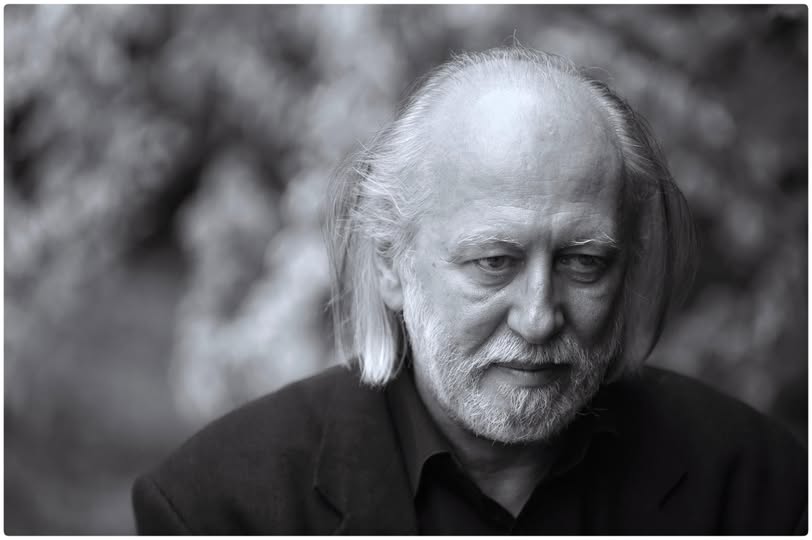

László Krasznahorkai

Như đã dự cảm trong một status tôi viết cách đây hai tuần, linh cảm ấy hôm nay trở thành hiện thực. Ngày 9 tháng 10 năm 2025, Viện Hàn lâm Thụy Điển đã chính thức công bố Giải Nobel Văn chương năm nay thuộc về nhà văn Hungary László Krasznahorkai. Trong thông cáo chính thức, Viện viết: “for his compelling and visionary oeuvre that, in the midst of apocalyptic terror, reaffirms the power of art”. Nghĩa là: “vì một sự nghiệp sáng tác đầy sức thuyết phục và tầm nhìn tiên tri, trong đó, giữa nỗi kinh hoàng của tận thế, ông vẫn khẳng định quyền năng của nghệ thuật”. Tuyên bố ấy là một tóm lược súc tích cho toàn bộ hành trình sáng tạo của Krasznahorkai: một nhà văn của bóng tối nhưng vẫn trung thành với ánh sáng; một người viết giữa hoang tàn nhưng vẫn gìn giữ phẩm giá của ngôn từ như hình thức tồn tại cuối cùng. Trong khoảnh khắc ấy, thế giới văn học không chỉ chứng kiến sự vinh danh một cá nhân mà còn chứng kiến lời xác tín rằng giữa hỗn loạn và lãng quên, vẫn còn những người tin vào sức cứu rỗi của chữ nghĩa.

Thế giới văn chương đón nhận tin ấy với cảm giác vừa bất ngờ vừa tất yếu. Ở tuổi bảy mươi mốt, Krasznahorkai không còn xa lạ trong giới phê bình quốc tế, song sự công nhận đến từ Viện Hàn lâm vẫn tạo nên một chấn động. Bởi lẽ, với nhiều độc giả, ông là một tác giả khó đọc, thậm chí khắc nghiệt. Văn chương của ông không chiều chuộng vỗ về, không gợi hứng khởi dễ dãi; nó đòi hỏi người đọc phải kiên nhẫn, phải cùng ông đi qua những mê lộ dằng dặc của ý thức và bóng tối. Việc ông được vinh danh vì thế không chỉ là chiến thắng của một cá nhân mà còn là chiến thắng của một quan niệm văn chương kiên định với cái khó, cái phức tạp và cái bất an trong tinh thần con người hiện đại.

László Krasznahorkai sinh năm 1954 tại Gyula, một thị trấn nhỏ miền đông Hungary gần biên giới Romania. Ông trưởng thành trong bối cảnh Đông Âu vẫn đắm mình trong sự trì trệ của chế độ xã hội chủ nghĩa. Học luật và văn học nhưng sớm chọn con đường biệt lập, ông tránh xa đời sống chính trị và văn hóa chính thống. Việc bị hạn chế di chuyển, bị kiểm duyệt và cô lập đã sớm khiến ông hiểu rằng tự do đích thực chỉ còn tồn tại trong không gian ngôn từ. Văn chương, với ông, là hành trình đi vào bóng tối của thế giới, nơi đổ vỡ và trống rỗng không thể cứu rỗi bằng ảo tưởng tiến bộ. Chính trong bối cảnh ấy, năm 1985, ông xuất bản Sátántangó, cuốn tiểu thuyết đầu tiên và cũng là cột mốc mở đầu cho toàn bộ vũ trụ sáng tác sau này.

Sátántangó kể về một cộng đồng nhỏ đang tan rã trong cơn mưa không dứt, nơi những con người kiệt quệ cố gắng tìm kiếm một hình thức cứu rỗi. Nhưng điều khiến tác phẩm trở thành hiện tượng không phải là cốt truyện mà là cách viết. Những câu văn dài đến hàng chục trang, không dấu chấm, không ngừng trôi theo dòng ý thức. Đọc Krasznahorkai không phải là đọc một câu chuyện, mà là bị cuốn vào một cơn lũ ngôn ngữ. Cái mệt mỏi, cái choáng váng ấy chính là chủ đích của ông: ngôn từ phải tự thân tái tạo cảm giác suy kiệt và tuyệt vọng của tồn tại.

Đạo diễn Béla Tarr, người bạn tri kỉ, đã chuyển thể Sátántangó thành bộ phim dài hơn bảy tiếng, một trong những tác phẩm điện ảnh ám ảnh nhất thế kỉ 20. Sự kết hợp ấy không chỉ là gặp gỡ nghệ thuật mà còn là sự cộng hưởng giữa hai cái nhìn triệt để: thế giới không có trung tâm, thời gian là vòng luân hồi và con người trong nỗ lực tìm ý nghĩa chỉ càng lún sâu vào mê lộ. Ở Krasznahorkai điều ấy được thể hiện bằng chữ, ở Tarr bằng hình ảnh; cả hai cùng sử dụng sự chậm rãi và dài dòng như một phương tiện phản kháng – phản kháng tốc độ, phản kháng nền văn hóa tiêu thụ, phản kháng sự rút ngắn của trải nghiệm tinh thần.

Từ Sátántangó, ông mở rộng thế giới của mình qua The Melancholy of Resistance, War and War, Seiobo There Below và Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming. Mỗi tác phẩm là một biến thể của cùng một ám ảnh: sự suy tàn của nhân loại. Nhân vật của ông thường là những kẻ cô độc, linh mục lạc lối, trí thức thất bại, lữ khách vô định, những bóng người lạc giữa thành phố sụp đổ và viện bảo tàng hoang lạnh. Dù bối cảnh thay đổi, từ làng quê Hungary đến Kyoto hay Bắc Kinh, nhưng cảm thức chung vẫn không đổi. Con người đang sống trong thời đại mà mọi hệ thống niềm tin truyền thống đều đổ vỡ, còn nghệ thuật chỉ còn lại như mảnh vụn mong manh để bấu víu.

Đọc Krasznahorkai là bước vào một thế giới không còn ranh giới giữa tôn giáo, triết học và văn chương. Câu chữ của ông mang nhịp điệu của lời cầu nguyện, nhưng đồng thời có cấu trúc của một suy tưởng triết lí. Ông chịu ảnh hưởng Kafka, Musil, Dostoevsky, nhưng mở rộng tầm nhìn đến triết học Phật giáo và mĩ học phương Đông. Trong những năm sống ở Nhật, ông từng nói mình tìm thấy “ý niệm về tĩnh lặng như một hình thức nhận thức”. Tĩnh lặng, trong ông, là cách đối diện với hỗn loạn. Nhờ đó, thế giới của ông vừa mang âm hưởng Kinh Thánh, vừa phảng phất hơi thở thiền định. Nếu Kafka viết về sự phi lí của hệ thống, thì Krasznahorkai viết về sự phi lí của chính linh hồn, ở đó ý thức con người vừa là nạn nhân, vừa là công cụ của sự đày ải.

Giải Nobel năm nay trao cho ông không chỉ vì một tác phẩm mà vì toàn bộ hành trình ấy. Bốn thập niên kiên trì với một mĩ học khắc khổ. Thông điệp của Viện Hàn lâm — “trong cơn hoảng loạn tận thế, ông khẳng định quyền năng của nghệ thuật” — không chỉ mô tả văn nghiệp mà là phác họa tư thế tồn tại. Krasznahorkai là người nhắc thế giới rằng văn chương không chỉ để an ủi, mà còn để làm ta sợ hãi, để đẩy ta ra khỏi vùng an toàn. Trong thời đại mọi thứ bị rút gọn thành mẩu tin, thành clip ngắn, việc tôn vinh một nhà văn của những câu dài vô tận là tuyên ngôn cho chiều sâu, cho sự chậm rãi, cho sức chịu đựng của tư tưởng.

Sự dấn thân ấy không chỉ nằm trong cấu trúc chữ nghĩa mà còn trong cách sống. Ông ẩn dật, tránh xa đám đông, không mạng xã hội, không phát biểu chính trị. Cuộc đời ông là hành trình di trú giữa Berlin, Kyoto, Bắc Kinh, Budapest, không phải để tìm nơi chốn, đó là để chứng nghiệm sự vô trú. Trong nhiều cuộc trò chuyện, ông luôn nói rằng viết là hình thức khổ hạnh, là việc đối mặt với sự bất lực của ngôn ngữ, bóng tối của tư tưởng và chính nỗi cô đơn của mình. Chính vì vậy mà văn chương của ông, dù trĩu nặng, vẫn mang tính thiêng liêng. Nó nhắc ta nhớ rằng ngôn từ, khi được đẩy đến giới hạn, có thể trở thành một con đường giải thoát.

Giải Nobel dành cho László Krasznahorkai không chỉ tôn vinh một cá nhân mà còn đánh dấu sự trở lại của tiếng nói Đông Âu trong đời sống tinh thần của nhân loại. Đây là vùng đất từng sản sinh nhiều nhà văn vĩ đại, nhưng trong những thập niên gần đây dường như bị khuất lấp bởi làn sóng Anglo-American. Từ Imre Kertész đến Olga Tokarczuk, văn chương Đông Âu luôn mang trong mình ba mạch ngầm chủ đạo: ý thức lịch sử như một định mệnh, cảm thức tội lỗi như một hình thái tự vấn và khát vọng siêu hình như phần còn lại của linh hồn sau đổ nát. Ở Krasznahorkai, ba dòng chảy ấy hội tụ thành một giọng nói riêng, nơi lịch sử, triết học và hiện sinh không tách rời mà hòa tan vào nhau như những tầng trầm tích của cùng một hệ ý thức. Ông không kể lại lịch sử mà để lịch sử thấm vào từng hơi thở của nhân vật. Ông không trình bày triết học mà để triết học tự vận hành trong cấu trúc của câu chữ. Ông không nói về tội lỗi như một phạm trù đạo đức. Ông xem nó như bản chất của tồn tại, như chiếc bóng đổ không thể rời khỏi thân người.

Văn chương của ông là hành trình song song giữa hủy diệt và cứu chuộc. Mỗi tiểu thuyết mở ra như một cơn mộng kéo dài, cho phép người đọc dò dẫm từng bước đi giữa sương mù của ý niệm. Khi kết thúc, ta không được giải thoát, nhưng ta thay đổi. Ta hiểu rằng cái đẹp không phải là hoàn hảo mà là sự kiên nhẫn tồn tại giữa đổ nát. Đó cũng là ý nghĩa sâu xa của việc Nobel 2025 chọn ông. Giữa thế giới đầy chiến tranh và khủng hoảng niềm tin, văn chương của ông nhắc ta về sức chịu đựng của tinh thần, rằng giữa tuyệt vọng vẫn còn một ánh sáng nhỏ nhoi, và chính ánh sáng ấy cứu rỗi.

Trong buổi họp báo tại Frankfurt, Krasznahorkai nói rằng “mọi sự công nhận đều tạm thời, còn cái bóng của ngôn ngữ thì vẫn kéo dài”. Câu nói ấy không chỉ phản ánh khiêm nhường mà còn cho thấy ông hiểu bản chất của danh vọng: vinh quang phai nhạt, chỉ văn chương còn lại. Giải Nobel này, nhìn rộng hơn, là tuyên bố rằng thời đại kĩ thuật số chưa thể giết chết văn chương nghiêm cẩn. Trong khi thế giới bị cuốn vào tốc độ, vẫn có người như ông, cần mẫn khắc ghi từng câu, tin rằng chậm rãi là kháng cự. Đọc ông, ta học lại cách đọc, lắng nghe và im lặng.

Bởi thế mà nhiều nhà phê bình gọi Krasznahorkai là “người canh giữ ngọn lửa cuối cùng”. Ông không đại diện cho trào lưu nào, nhưng giữ được phẩm chất hiếm hoi: lòng tin tuyệt đối vào ngôn ngữ. Nếu văn chương đánh mất niềm tin ấy, nó chỉ còn là giải trí; còn với ông, viết vẫn là một thực hành nghi lễ, một hành động linh thiêng, một cách con người chạm đến vực sâu của chính mình.

Giải Nobel Văn chương 2025, xét đến cùng, không chỉ là sự tôn vinh dành cho một cá nhân, đó mà còn là một tuyên ngôn về giá trị của sự kiên định trong sáng tạo. Trong một thế giới đang bị ám ảnh bởi tốc độ và sự giản lược, việc vinh danh một nhà văn của bóng tối và tư tưởng là hành động can đảm, một sự khẳng định rằng văn học vẫn còn chỗ cho những tiếng nói không thỏa hiệp. Bởi chính trong vùng bất an, cái đẹp mới tìm được nền tảng của mình; và đôi khi, chỉ qua những câu văn dài như một nhịp thở cuối cùng, ta mới có thể lắng nghe được âm vang sâu thẳm nhất của nhân tính.

Khi đêm xuống, người ta có thể hình dung ông ngồi trong căn phòng nhỏ ở Berlin hay Budapest, viết tiếp một câu chưa dứt từ mười năm trước. Ngoài kia, thế giới vẫn ồn ào. Còn trong căn phòng ấy, một người đàn ông vẫn cặm cụi với cây bút của mình, tin rằng trong những câu chữ dài vô tận kia, vẫn còn một thứ ánh sáng nhỏ nhoi nhưng bền bỉ, soi rọi bóng tối của thời đại.

- •••

László Krasznahorkai: Une lumière dans le ténèbres

Comme je l’avais pressenti dans une réflexion publiée deux semaines plus tôt, l’intuition s’est aujourd’hui accomplie. Le 9 octobre 2025, l’Académie suédoise a annoncé que le prix Nobel de littérature revenait à l’écrivain hongrois László Krasznahorkai. Dans son communiqué, elle précise: “Pour une œuvre d’une force de conviction et d’une vision singulières, qui, au cœur de la terreur apocalyptique, réaffirme la puissance de l’art”. Cette formule condense l’essentiel de son parcours: un écrivain des ténèbres demeuré fidèle à la lumière; un homme qui, parmi les ruines, continue de préserver la dignité du verbe comme ultime forme d’existence. En ce moment précis, le monde des lettres n’assiste pas seulement à la consécration d’un individu, mais à la réaffirmation qu’au milieu du chaos et de l’oubli subsistent encore ceux qui croient au pouvoir rédempteur des mots.

Le milieu littéraire a accueilli la nouvelle avec un mélange d’étonnement et d’évidence. À soixante-et-onze ans, Krasznahorkai n’est plus un inconnu pour la critique internationale; pourtant, la reconnaissance venue de Stockholm a résonné comme un séisme silencieux. Pour beaucoup, il demeure un auteur ardu, parfois intransigeant. Sa prose ne caresse ni ne console; elle exige patience et persévérance, engageant le lecteur à traverser avec lui les labyrinthes de la conscience et de l’ombre. La distinction qui lui est accordée n’est donc pas seulement celle d’un homme, mais celle d’une conception rigoureuse de la littérature, fidèle à la complexité, à la difficulté et à l’inquiétude constitutives de l’esprit moderne.

Né en 1954 à Gyula, petite ville de l’est hongrois près de la frontière roumaine, Krasznahorkai grandit dans la lenteur étouffante du régime socialiste. Après des études de droit et de lettres, il choisit très tôt la solitude, se tenant à distance des circuits politiques et culturels officiels. Les restrictions, la censure, l’isolement lui révèlent que la liberté véritable ne subsiste que dans l’espace du langage. Pour lui, la littérature devient un chemin vers la nuit du monde, là où la ruine et le vide ne sauraient être sauvés par l’illusion du progrès. C’est dans cette obscurité que paraît, en 1985, Sátántangó, premier roman et pierre angulaire d’un univers d’écriture appelé à se déployer.

Sátántangó raconte la lente décomposition d’une petite communauté sous une pluie sans fin, où des êtres épuisés cherchent encore une improbable rédemption. Mais l’essentiel n’est pas dans l’intrigue: il réside dans la phrase. Des périodes interminables, courant sur des pages entières, sans répit ni ponctuation, comme un fleuve de conscience. Lire Krasznahorkai, c’est moins suivre un récit que se laisser emporter par une crue verbale. Ce vertige, cette fatigue sont voulus: la phrase doit, par sa propre tension, recréer l’épuisement et le désespoir de l’existence.

Le cinéaste Béla Tarr, son ami et compagnon de route, a adapté Sátántangó dans un film de plus de sept heures, devenu l’une des œuvres les plus saisissantes du vingtième siècle. Leur rencontre dépasse la collaboration artistique: elle consacre une même vision du monde – un univers sans centre, un temps circulaire, un homme qui, cherchant le sens, s’enfonce dans le labyrinthe de sa propre conscience. Chez Krasznahorkai, cette vision s’exprime par la langue; chez Tarr, par l’image. Tous deux font de la lenteur et de la durée une forme de résistance: résistance à la vitesse, à la consommation, à la contraction de l’expérience intérieure.

À partir de Sátántangó, Krasznahorkai déploie son cosmos: The Melancholy of Resistance, War and War, Seiobo There Below, Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming. Chaque œuvre en constitue une variation: la lente agonie du monde, la dérive de l’esprit, la chute du sacré. Ses personnages, solitaires, prêtres égarés, intellectuels déchus, voyageurs sans destination, errent parmi des villes en ruine et des musées désertés. Les lieux changent – la Hongrie, Kyoto, Pékin – mais la tonalité demeure: l’humanité vit l’époque où tout système de croyance s’effondre, où l’art n’est plus qu’un fragment fragile auquel se raccrocher.

Lire Krasznahorkai, c’est pénétrer dans un espace où religion, philosophie et littérature se confondent. Sa syntaxe épouse le rythme de la prière et la rigueur du raisonnement. Héritier de Kafka, Musil, Dostoïevski, il étend sa méditation jusqu’à la philosophie bouddhique et à l’esthétique orientale. Lors de ses années au Japon, il a confié y avoir découvert “l’idée du silence comme forme de connaissance”. Le silence, pour lui, est manière d’affronter le chaos. Ainsi, son univers conjugue résonance biblique et souffle méditatif. Si Kafka écrivait l’absurde des systèmes, Krasznahorkai écrit l’absurde de l’âme: une conscience qui est tout à la fois victime et instrument de son propre supplice.

Le Nobel 2025 couronne non pas un livre, mais un itinéraire: quatre décennies de fidélité à une esthétique ascétique. Le message de l’Académie — “au milieu de la panique apocalyptique, il affirme la puissance de l’art” — esquisse moins une carrière qu’une posture d’existence. Krasznahorkai rappelle au monde que la littérature ne sert pas seulement à consoler, mais à effrayer, à déranger, à nous chasser hors de la zone de confort. À une époque où tout se réduit à des fragments, des nouvelles instantanées, des vidéos éphémères, célébrer un écrivain des phrases interminables revient à proclamer la valeur de la lenteur, de la profondeur, de l’endurance de la pensée.

Son engagement ne réside pas uniquement dans la structure de la phrase, mais dans la manière d’être au monde. Solitaire, rétif aux foules, absent des réseaux sociaux et des tribunes publiques, il mène une vie d’errance entre Berlin, Kyoto, Pékin et Budapest — non pour trouver un lieu, mais pour éprouver le non-lieu. Dans de nombreux entretiens, il confie que l’écriture est une ascèse: affronter l’impuissance du langage, les ténèbres de la pensée, la solitude radicale. C’est pourquoi sa prose, si dense, garde une dimension sacrée. Elle nous rappelle que le langage, poussé à sa limite, devient un chemin de libération.

Le Nobel attribué à Krasznahorkai ne célèbre donc pas seulement un individu: il marque le retour de la voix d’Europe de l’Est dans la conscience spirituelle du monde. Cette région, jadis foyer de grandes figures littéraires, semblait ces dernières décennies éclipsée par la domination anglo-américaine. De Imre Kertész à Olga Tokarczuk, les lettres d’Europe centrale ont toujours été traversées par trois courants essentiels: la conscience de l’histoire comme fatalité, le sentiment de culpabilité comme interrogation existentielle, et le désir métaphysique comme dernier souffle de l’âme après la chute. Chez Krasznahorkai, ces trois lignes convergent en une voix unique, où l’histoire, la philosophie et l’existence se fondent en une même matière. Il ne raconte pas l’histoire, il la laisse s’infiltrer dans la respiration de ses personnages. Il ne théorise pas la philosophie, il la fait vibrer dans la syntaxe. Il ne parle pas de la faute comme d’une catégorie morale. Il la considère comme l’essence même de l’être, comme l’ombre indétachable du corps humain.

Son œuvre est une traversée parallèle de la destruction et de la rédemption. Chaque roman s’ouvre comme un rêve prolongé, où le lecteur avance pas à pas dans la brume des idées. À la fin, il n’est pas délivré, mais transformé: il découvre que la beauté n’est pas perfection, mais persistance au sein des ruines. Tel est le sens profond du choix de Krasznahorkai par le Nobel 2025. Dans un monde ravagé par la guerre et la perte de foi, sa littérature rappelle la résistance de l’esprit, la survivance d’une lumière infime, mais tenace, capable encore de sauver.

Lors de la conférence de presse de Francfort, Krasznahorkai a déclaré: “Toute reconnaissance est provisoire ; seule l’ombre du langage demeure”. Cette phrase, empreinte d’humilité, témoigne aussi d’une lucidité aiguë sur la nature de la gloire: la renommée s’efface, seule la littérature perdure. Ce Nobel proclame que l’ère numérique n’a pas encore tué la rigueur du verbe. Tandis que le monde s’abandonne à la vitesse, lui reste là, penché sur la phrase, convaincu que la lenteur est une forme de résistance. Le lire, c’est réapprendre à lire, à écouter, à se taire.

C’est pourquoi tant de critiques le nomment “le gardien de la dernière flamme”. Il ne représente aucune école, mais incarne une vertu rare: la foi absolue dans le langage. Si la littérature perd cette foi, elle n’est plus qu’un divertissement; pour lui, écrire demeure un rite, un acte sacré, une manière pour l’homme de frôler l’abîme de lui-même.

Le prix Nobel de littérature 2025 n’est donc pas seulement une récompense: il est une déclaration sur la valeur de la persévérance créatrice. Dans un monde obsédé par la vitesse et la simplification, honorer un écrivain des ténèbres et de la pensée est un geste de courage, une affirmation que la littérature a encore une place pour les voix intransigeantes. Car c’est dans l’inquiétude que la beauté trouve sa base, et parfois, ce n’est qu’à travers des phrases longues comme un dernier souffle que l’on peut entendre l’écho le plus profond de l’humanité.

Lorsque la nuit tombe, on peut l’imaginer assis dans une petite chambre à Berlin ou à Budapest, poursuivant une phrase restée inachevée depuis dix ans. Dehors, le monde demeure bruyant. Là, dans la pénombre, un homme continue d’écrire, convaincu que dans la lente lumière de ses phrases interminables persiste une clarté fragile mais obstinée, capable d’éclairer les ténèbres de notre époque.

- •••

László Krasznahorkai:

As I had foreseen in a reflection written two weeks earlier, that intuition has now been fulfilled. On October 9, 2025, the Swedish Academy officially announced that the Nobel Prize in Literature had been awarded to the Hungarian novelist László Krasznahorkai. In its statement, the Academy wrote, “For a body of work of exceptional conviction and vision that, at the heart of apocalyptic terror, reaffirms the power of art”. That sentence distills the essence of his entire journey: a writer of darkness who has remained faithful to light, a man who, amid the ruins, continues to safeguard the dignity of language as the final form of existence. At that moment, the literary world didn’t merely witness the consecration of an individual but the reaffirmation that within chaos and oblivion there still exist those who believe in the redemptive power of words.

The literary community greeted the news with both surprise and inevitability. At seventy-one, Krasznahorkai is no stranger to international criticism, yet the recognition from Stockholm still reverberated like a silent earthquake. To many readers he remains a difficult, even austere writer. His prose neither soothes nor flatters; it demands patience and endurance, compelling the reader to traverse with him the labyrinths of consciousness and shadow. His award thus represents not only the triumph of an individual, but the vindication of a vision of literature that resists simplicity, welcomes complexity, and dares to face the restless depths of the modern soul.

Born in 1954 in Gyula, a small town in eastern Hungary near the Romanian border, Krasznahorkai came of age within the stifling immobility of the socialist regime. After studying law and literature, he chose solitude early, distancing himself from political and cultural orthodoxy. Restrictions, censorship, and isolation soon revealed to him that true freedom survived only within language. Literature, for him, became a journey into the night of the world, where ruin and emptiness can no longer be redeemed by the illusion of progress. It was within that darkness that in 1985 Sátántangó appeared, his first novel and the cornerstone of an entire imaginative universe.

Sátántangó tells of a small, decaying community under ceaseless rain, its exhausted inhabitants still seeking an impossible salvation. Yet what makes the work extraordinary lies not in its plot but in its form: sentences stretching over pages without pause or punctuation, a relentless current of consciousness. Reading Krasznahorkai is less to follow a story than to be carried away by a verbal flood. The fatigue, the vertigo, are deliberate. Through the strain of syntax itself, language must recreate the exhaustion and despair of existence.

The filmmaker Béla Tarr, his close friend and artistic twin, adapted Sátántangó into a film of more than seven hours, one of the most haunting cinematic works of the twentieth century. Their collaboration transcends art; it reveals a shared metaphysical vision, a world without center, a time that loops, a humanity that in its search for meaning sinks deeper into the labyrinth of its own mind. In Krasznahorkai this vision is expressed through language; in Tarr, through image. Both transform slowness and duration into acts of resistance, resistance to speed, to consumption, to the contraction of inner experience.

From Sátántangó onward, Krasznahorkai expanded his cosmos: The Melancholy of Resistance, War and War, Seiobo There Below, Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming. Each work offers a variation on the same obsession, the slow agony of the world, the drift of the spirit, the collapse of the sacred. His characters, solitary figures, lost priests, defeated intellectuals, wanderers without destination, move through ruined cities and desolate museums. The settings change, from Hungary to Kyoto to Beijing, but the tonality endures. Humanity now inhabits an age where every traditional system of belief has fallen, and art remains only as a fragile shard to cling to.

To read Krasznahorkai is to enter a space where religion, philosophy, and literature converge. His syntax carries both the rhythm of prayer and the discipline of thought. Heir to Kafka, Musil, and Dostoevsky, he extends his meditation toward Buddhist philosophy and Eastern aesthetics. During his years in Japan, he confessed that he had discovered “the idea of silence as a form of knowledge”. Silence, for him, is a way of confronting chaos. His world therefore unites biblical resonance with meditative breath. If Kafka wrote the absurdity of systems, Krasznahorkai writes the absurdity of the soul, a consciousness that is both victim and instrument of its own torment.

The 2025 Nobel Prize crowns not a single book but an entire journey, four decades of ascetic fidelity to an uncompromising aesthetic. The Academy’s message, “in the midst of apocalyptic panic he affirms the power of art”, sketches less a career than a stance of being. Krasznahorkai reminds the world that literature is not meant only to console but also to terrify, to unsettle, to cast us beyond the comfort zone. In an age that reduces everything to fragments, instant news, and fleeting clips, the celebration of a writer of endless sentences becomes a declaration of the value of slowness, of depth, of the endurance of thought.

His commitment resides not only in the structure of his sentences but in his way of inhabiting the world. Reclusive, allergic to crowds, absent from social media and public posturing, he leads a nomadic life between Berlin, Kyoto, Beijing, and Budapest, not to find a home but to experience non-belonging. In many conversations he has said that writing is a form of asceticism, to face the impotence of language, the darkness of thought, and one’s own solitude. Hence his prose, for all its density, retains a sacred aura. It reminds us that language, when pushed to its limit, can become a path to liberation.

The Nobel awarded to Krasznahorkai doesn’t merely honor an individual; it marks the return of the Eastern European voice to the spiritual consciousness of the world. This region, once home to towering literary figures, had in recent decades seemed eclipsed by the Anglo-American wave. From Imre Kertész to Olga Tokarczuk, Central European literature has always carried three subterranean currents: the awareness of history as destiny, the sense of guilt as existential inquiry, and the metaphysical yearning as the soul’s last breath after destruction. In Krasznahorkai these three lines converge into a singular voice where history, philosophy, and existence fuse into one substance. He doesn’t recount history; he allows it to seep into the breathing of his characters. He doesn’t theorize philosophy; he makes it vibrate within syntax. He doesn’t treat guilt as a moral category; he regards it as the very essence of being, the shadow inseparable from the human body.

His body of work is a parallel crossing between destruction and redemption. Each novel opens like a prolonged dream through which the reader gropes within the mist of ideas. At the end one is not delivered but transformed, realizing that beauty is not perfection but persistence amid ruin. This is the deeper meaning of the Nobel Committee’s choice in 2025. In a world ravaged by wars and the loss of faith, his literature reminds us of the endurance of the spirit, that even within despair there remains a faint yet tenacious light capable still of saving.

At the Frankfurt press conference, Krasznahorkai remarked, “all recognition is temporary; only the shadow of language endures”. The sentence, filled with humility, also reveals a sharp lucidity about the nature of glory: fame fades, only literature remains. This Nobel declares that the digital age hasn’t yet killed the rigor of the word. While the world surrenders to speed, he bends again over his sentence, convinced that slowness itself is a form of resistance. To read him is to relearn how to read, how to listen, and how to be silent.

That is why so many critics call Krasznahorkai the guardian of the last flame. He represents no school yet embodies a rare virtue, an absolute faith in language. If literature loses that faith, it becomes mere entertainment; for him, writing remains a rite, a sacred act, a way for human beings to brush against the abyss of themselves.

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Literature is therefore not merely a reward; it’s a declaration of the value of creative perseverance. In a world obsessed with speed and simplification, honoring a writer of darkness and thought is an act of courage, an affirmation that literature still has room for uncompromising voices. For it is within disquiet that beauty takes root, and sometimes only through sentences as long as a final breath can we hear the deepest echo of humanity.

When night falls, one can imagine him seated in a small room in Berlin or Budapest, continuing a sentence left unfinished ten years ago. Outside the world remains noisy. Inside that dimly lit room a man keeps writing, believing that within those endlessly unfolding sentences there persists a fragile but stubborn light that continues to illuminate the darkness of our time.

— Tino Cao, Washington, 9 Oct 2025